Twelve-tone Applications of "Apparent Poly-tonality"

Nancy Lee Harper

When the name of the Spanish composer Manuel de Falla (1876-1946) is mentioned, his popular works such as La Vida Breve, El Amor Brujo, Las Noches en los Jardines de España, and Siete Canciones Populares Españolas immediately come to mind. And naturally the question arises, "What has his music to do with the more abstract twelve-tone techniques?" Little is known of de Falla's later works, such as Atlantida, or of his most important works El Retablo del Maese Pedro of 1923 and the Concerto of 1926, let alone the working processes of his complex mind. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to shed light on how de Falla's evolutionary compositional processes were continued by his student, Rodolfo Halffter (1900-1987), Mexico's first dodecaphonic composer.

For the reader who is not familiar with the life and works of Rodolfo Halffter, nor the terms Superposiciones ("Superpositions"), "apparent poly-tonality," and "internal rhythm," a brief explanation follows.

Spain in the 1920's was ripe for artistic change. Desiring to create a new Spanish nationalistic artistic language, several artists, poets, and musicians (among them Salvador Dali, Federico and Francisco Garcia Lorca, and Manuel de Falla) formed an alliance dedicated to this lofty goal and to celebrating the 300th anniversary of Spain's great poet Luis de Góngora (d. 1627). Certainly for music, Spain's golden age of polyphony of the 16th century had never been surpassed. It was time, the Gongorists declared, to renew and redefine their artistic language while yet retaining their "Spanishness."

It was in this artistic climate that Rodolfo Halffter found himself as a young man. He was born in Madrid on October 30, 1900, to a Junker family whose father was Prussian, while his Catalan mother hailed from Barcelona. Although Halffter desired to be a composer from an early age, he was encouraged to do something more practical and so became a banker. Essentially an auto-didact, Halffter sought out contemporary currents and composers from which to learn, including the works of Claude Debussy and the Halmonielehre of Arnold Schoenberg. Halffter described his own early compositions as "within chromaticisn and tonal vagueness," admitting that for Spain they represented isolated incidences of atonality.1

Halffter was perhaps well on his way to becoming Spain's first twelve-tone composer when he was introduced to de Falla in the 1920's by the composer musicologist Adolfo Salazar. Halffter commented, "Instantaneously I accepted the teachings of (de) Falla (sic) which in part represented everything to the contrary which

I had believed until that moment .... (The adoption of) neoclassicism was a kind of conversion as a result of knowing (de) Falla." (sic) (Ibid) And in this spirit, Halffter, along with his brother Ernesto, and six other young composers formed their own "Grupo de Ocho" (Group of Eight) dedicated to new music of twentieth-century Spain.

Sometime in the early 1900's (authorities do not agree on the date) de Falla chanced upon a book in a second-hand bookstore in the Cuesta. de Moyano in front of the Botanical Gardens in Madrid. The book, L'Acoustique Nouvelle, ou Essai d'application d''une métode philosophique aux questions élevées de l'Acoustique, e la Musique et de la Composition musicale by Frenchman Louis Lucas and published in the second edition in 1854, would have a great impact upon de Falla. From it comes both the concept of 11apparent polytonality" and "internal rhythm" as de Falla would develop them.

2Halffter explained that de Falla "cortó el camiño" (shortened the path), meaning that de Falla never used any musical materials excessively.

3 The term "internal rhythm" can be explained as "shortening the path," structurally destroying the "squareness" of symmetrical phrases. "Just as it is impossible to excel the contrapuntal mastery of Bach," Falla said, "it will be impossible for anyone to surpass the internal rhythm of Scarlatti." 4The concept of "apparent poly-tonality" comes from the generator- resonance theories of Lucas, who often quoted the harmonic theories of Jean-Philippe Rameau. To greatly simplify, from the "mirror" examples derived from C Major the potential polytonal combinations of F minor and G Major result.

5Example 1: C major generator triad and two potential poly-tonal resonances.

De Falla's harmonic system, which he terms "superpositions," is naively simple. To begin with, he remains completely faithful to tonality and never uses chords other than major or minor, mostly in their disjunct forms. Only chord tones (root, third, or fifth) are used to generate the new resonances with the addition of various kinds of 5ths (perfect, augmented, or diminished). The plus sign (+) is used to generate the new resonance above and the minus sign (-) is used to calculate the resonance from below the generator. The plus sign is also used to indicate an augmented triad while the minus sign is also used to indicate a diminished triad. (For the purposes of this article a small 11o" will be used to indicate a diminshed triad.) Octave equivalencies hold in de Falla's system. Whole notes indicate the generator while filled-in notes indicate the resulting resonances.

The document entitled Superposiciones (Superpositions) was published in 1975 and gives a representation of de Falla's system.6 For example, from a minor triad

C-E![]() -G, (on Page 1, Number I from now on referred to as P1, N1, see Example 2 below) de Falla generates the resonances of A

-G, (on Page 1, Number I from now on referred to as P1, N1, see Example 2 below) de Falla generates the resonances of A ![]() - and D by using the formula 5+5, 3-5. This means that to the fifth of the chord, the note G, is added another perfect 5th, thereby resulting in D; and to the third of the chord, the note E

- and D by using the formula 5+5, 3-5. This means that to the fifth of the chord, the note G, is added another perfect 5th, thereby resulting in D; and to the third of the chord, the note E![]() -, is subtracted a perfect fifth, thereby resulting in the note A

-, is subtracted a perfect fifth, thereby resulting in the note A ![]() -.

-.

Example 2: Superposiciones, P1, N1 (page 1, number 1)

In the next example, de Falla uses three formulas to generate a six-note chord.

Example 3: Superposiciones, 6-note chord from p.1, P1, N22.

Another example can be seen in one of de Falla's middle period works in the opening chords of the Concerto.

Example 4: Concerto, 1st movement, ms. 1 (ot in Superposiciones.)

The concepts of superpositions and apparent poly-tonality deal with

harmonic aspects, while the concept of internal rhythm obviously deals with phrase

lengths, structure, and rhythm. With regard to melody, de Falla often used literary or folksong sources as an inspiration. 7 Often there is little or no motivic or melodic

development in de Falla works. Slight alterations in rhythm or texture will be made as in the Siete Canciones Populares Españolas, or the repetition of a melody in canon will be found, especially the canon at the interval of the second or third, as in the first movement of the Concerto which is based on the folksong "De los alamos vengo, madre." De Falla is similar to his friend Igor Stravinsky in this aspect of little melodic/motivic development.

Having examined some of de Falla's compositional techniques, the question arises, "How did Halffter use and evolve the compositional processes of rhythm, harmony, melody, and musical form?" As has been mentioned, Halffter completely moved away from his initial atonal style in favor of poly-tonality, as a result of knowing de Falla. He began composing in a neo-classic style using poly-tonality without the benefit or exact knowledge of the Superposiciones. In the second of Dos Sonatas de El Escorial the opening chord may be considered as resultant from the generator- resonance idea (Example 5). Indeed, de Falla gave Halffter some advice during the composition of these sonatas, changing the left hand from a series of 4ths to the pattern below (Example 6).

In the successful ballet Don Lindo de Almería of 1935 Halffter instinctively used the generator-resonance concept without knowing of de Falla's Superposiciones.

Example 5: Dos Sonatas de El Escoria/ / lI, ms. 1.

Example 6: Dos Sonatas de El Escoria/ /, ms. 20-24.

In example 7 in the passage marked with the arrow, Halffter says, "Bitonal superpositions of B 6 major over B major, produced by the natural resonances of the 7th of the 17 chord of B major." In Halffter's example A, using the formula 3+5, 1-5o, he shows that the generator chord of B major produces the resonances of F, A, E

flat (D# converts to E![]() ), the V of B

), the V of B ![]() , . Example 7 is also based on the 7th chord as the pivot note or generator. Halffter entitles the analysis "Polytonal Superpositions (as examples) of Don Lindo de Almería, by Rodolfo Halffter. 8

, . Example 7 is also based on the 7th chord as the pivot note or generator. Halffter entitles the analysis "Polytonal Superpositions (as examples) of Don Lindo de Almería, by Rodolfo Halffter. 8

Example 7: Unpublished analysis of Don Lindo de Almería by Rodolfo Halffter, ms. 1-6. Prime D, 1, 3; Transposition 0, 1, 3; Inversion 0, 1, 3; Retrograde0, 2, 4 .

Halffter, who possessed a precise and open mind, continued to seek other compositional techniques. He attended some classes of Arnold Schoenberg in Barcelona in 1932. 9 In the late 1940's, having been exiled to Mexico as a result of the Spanish Civil War and become a naturalized Mexican citizen in 1939, Halffter began teaching twelvetone concepts to his students at the National Conservatory of Music in Mexico City. His first 12-tone piece, Tres Hojas de Album (Three Album Leaves) appeared in 1953. 10 Around 1958-59 he wrote to his composer-nephew, Cristóbal Halffter:

My position ... is the result of a long evolution because 1. believe, like you, that folkloric nationalism ... represents a blind alley ... and it is necessary to search for the national "being" by new roads .... Dodecaphony ... can be one of these ways .... The mistake of many critics and superficial listeners consists in affirming that all serial music has necessarily to sound like Schoenberg, its genius-inventor.

11

Example 8: Beethoven, Sonata, op.2/1, 3rd movement, ms. 1-8.

Did Halffter break completely with the ideas of de Falla in favor of those of Arnold Schoenberg? In order to answer this question, several of Halffter's twelve-tone works must be studied. Following are some of the most important characteristics observed:.

1 First and last movements of a work often begin with the same note or row form, suggesting a pitch center ( T lies HojRs ole Album - 1953 ; Laberinto - 1972 ).

2. Frequently the row form is constructed to contain an obvious juxtaposition of seventh chords, as used in Rodolfo's treatment of "apparent poly-tonality" (several works).

3. Manipulation of the row forms is used to create major and minor triads. (Nocturno-1973; Facetas - 1976).

4. Compositional challenges within the 12-tone system are found in the use of traditional figures, such as the ostinato (Sequencia - 1977) the glissando (Laberinto), and the appogiatura which is an inherent feature in cante jondo (Secuencia) and the trill (Escolio - 1980).

5., The invention of original notational symbols (Tercera Sonata para Piano or Third Piano Sonata of 1967).

6. Incomplete usage of the row, sometimes with the remainder of the row being used to begin another movement Secuencia).

7. Doubling of notes at the octave disregarding Schoenbergian rules (several works).

8. Unusual metric usage, reminiscent of "internal rhythm (Facetas).

9. Repetition of phrases or "reflected images" (many works).

10. Beginning a work with one of the other row forms instead of the original prime statement of the row (Tres Hojas de Album, see Example 9 below.)

11. The usage of two row forms thereby suggesting "apparent poly-tonality (Escolio).

Example 9: R. Halffier, Tres Hojas de Album, rns. 1-2, plus composer's explanation.

Suspicion that Halter's aesthetic ideal is still embedded in his Spanish roots and possibly in de Falla's "apparent poly-tonality" arises as early as his first 12-tone work Tres Hojas de Album (Example 9 above.) The fact that he begins this most "Schoenbergian " of all his pieces not with the original statement of the tone row but with its inversion, la and Ih (the first and eighth forms of the inversion as indicated by Halffter), belies any strict adherence to the German inventor's system.

And evidence grows with each new 12-tone piece. From 1953 on Halter not only wrote in the 12-tone language, but also in polytonality. At the end of his life he was even beginning to mix Mexican elements freely with the 12-tone system in his last work Paquilitzli for seven percussion instruments (1983).

Halffter's "Conjunto de Series" and Analysis of Escolio

After his death an unpublished and undated document entitled "Conjunto de Series" or "Groupings of the Series" was found, in which it is clear that Halffter was manipulating tone rows to manifest de Falla's ideas contained in the Superposiciones.12 Halffter states at the beginning of the work: "Grouping of Dodecaphonic Series projected and used by me." He goes on to say, "Observe, in some cases, the existing relationship between serial technique and the technique of the Superposiciones." He continues, "The chords (sonorous conglomerates) obtained through the simultaneous emission of the tones of the hexachords of a dodecaphonic series can also be explained, in some cases, as a result of the utilization of the technique of the Superposiciones (added tones)." 13

Halffter, following de Falla's system, uses only major or minor triads from each hexachord and its inversion to be the generator chord. Notice that he uses nonsequential numbers of the series to create the generator chords. The following examples show a variety of chords possible, including 7ths and 9ths.

The series on page 12 of the "Conjunto de Series," F A C# C E ![]() B/G B

B/G B ![]() F# E D G#, generates the following chords:

F# E D G#, generates the following chords:

Example 10a: Chords generated from F major triad (Numbers 1, 2, 4) from 1st hexachord on page 12 of "Conjunto de Series" with formula of 1+52, 1-5-, and 3 + 5-.

Example 10b: Chords generated from G minor, 2nd inversion triad. (Numbers 9, 10, 11) from the 2nd hexachord on page12 of "Conjunto de Series" with formula 3-52, 3+5+, 5-52.

From the inversion of the series on page 12 the following chords are derived:

Example 10c: Chords derived from B 6 minor triad (Numbers 1, 2, 4) from the inversion of the 1st hexachord on page 2 'of "Conjunto de Series" with formula 3-52, 3+5+, 5 52.</P

Twelve-tone Applications of >.E; and BA#G F#FC#/D# C E G# D A. As many of the chords derived are similar to examples 10a-10d, only examples pertinent to the analysis of

Escolio will be included elsewhere in the paper.

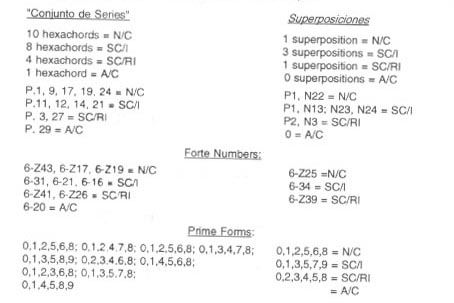

In comparing the "Conjunto de Series" with the Superposiciones, Halffter uses hexachords which are either non-com binatorial or semi-combinatorial by inversion in the majority of cases, while de Falla's prefers hexachords which are semi-combinatorial by inversion. The inversion factor in both instances is interesting, meaning that each hexachord "must be capable of inversion without revision of its content; (and) the content of one segment must be statable as the inversion of the content of the other. 14 The three Superposition chords (6-Z25, 6-34, 6-Z39) may be compared with certain of the "Conjunto chords. Although similar but distinct from each other the generator-resonance system demonstrates a great variety of possibilities, perhaps indicating that the Superposiciones is not a "theory of resonance" but a sampling of the myriad possibilities which exist within its realm. A comparison with the "Conjunto" hexachords and the 6-note chords from the Superposiciones reveals only a little information because of the few 6-note chords generated in the latter document. For example:

(N/C = non-combinatorial, SC/l = semi-combinatorial by inversion,

SC/Rl = semi-combinatorial by retrograde inversion and A/C = all combinatorial)

A preliminary investigation of Halffter's piano piece Escolio (see Appendix I for Halffter's manuscript with explanation of the hexachordal usage) now ensues for the following reasons: 1) it is the composer's next-to-last and most developed 12-tone piano piece; 2) it uses a theme from Homenaje a Debussy (1920) by de Falla; and 3) it uses two row forms, suggestive of "apparent poly-tonality." From the Spanish, Escolio means "a brief explanatory observation; a commentary; a note which refers to a preceding proposition."15 Thus, it is clear that Halffter is paying tribute to his mentor de Falla.

To begin with, de Falla's Homenaje a Debussy begins his piece with an F-EF motive (Example 11), while Halffter, with his characteristic humility and not wanting to seem "superior" to de Falla, begins the piece with the same motive a full step lower, while citing de Falla's motive above the beginning of his piece.

Example 11: Measures 1-3 of de Falla's Homenaje a Debussy.

Example 12: Opening of Halffter's Escolio.

In observing the two series of Escolio, the following characteristics may be seen:

Series A: G F# B B ![]() D D#/ G# C A E C# F (descending half-step motive)

D D#/ G# C A E C# F (descending half-step motive)

Series B: F# C# D G# B C/ E F G E ![]() A B

A B ![]() (ascending half-step motive)

(ascending half-step motive)

The half-step relationship between the first and second series is immediately obvious, like the leading tone to tonic relationship and suggestive of the half-step motive of the opening theme. More important than this apparent leading-tone to tonic relationship is the characteristic half-step descent of F-E found in the 1st tetrachord of the Phyrigian mode which is so typical of Spanish music. As will be shown, this half-step relationship, both ascending and descending, is the basis for Halffter's entire piece.

Series A corresponds to p. 5 in the "Conjunto de Series" (Appendix II) while Series B is found as p.3 in the same Appendix. The following characteristics of each row form may be determined as:

Series A: #6-20 (4) (Forte labeling);

all combinatorial;

prime form (0,1,4,5,8,9)

interval vector of [303630];

complement identical

What is of particular interest in this first series is the construction of the hexachords to contain three sets of half-step dyads each for a total of six.

Series B. #6-Z41;

semi-combinatorial by retrograde inversion;

prime form (0,1,2,3,6,8)

interval vector of [332232]

complement = 6-Z12 with prime form of (0,1,2,4,6,7;)

interval vector identical

In the Conjunto of Series no chordal constructions of this particular row form are made by Halffter. However, in the

1st hexachord of Series A a large number of chords ranging from major, minor, augmented and diminished to various types of 7th and 9th chords may be found. The 2nd tetrachord is less prolific, but nonetheless 12 chords of varying types maybe found. Series B has fewer harmonic potentials yielding at least two new chords not contained in either hexachord of Series A.

The following structural analysis of Escolio suggests an ABAB'A (codetta) Sonata Rondo form which functions as a Sonata form with Exposition/Development/ Recapitulation ("PT" indicating the primary theme and "ST will be used to indicate a diminished triad.) Octave equivalencies hold in de Falla's system. Whole notes indicate the generator while filled-in notes indicate the resulting resonances.

The document entitled Superposiciones (Superpositions) was published in 1975 and gives a representation of de Falla's system.(6) For example, from a minor triad

C-E![]() -G, (on Page 1, Number I from now on referred to as P1, N1, see Example 2 below) de Falla generates the resonances of A the series as retrograde-in version in ms.20, his numbering system is erroneously given as that of the inversion of the row form. Also, he continues to use only one numbering system. The numbers 1-12 are used for all forms with no corresponding numbering system being set up for the retrograde forms. For the purposes of this article Halffter's hexachord labeling will remain because it does. not affect the structural analysis.

-G, (on Page 1, Number I from now on referred to as P1, N1, see Example 2 below) de Falla generates the resonances of A the series as retrograde-in version in ms.20, his numbering system is erroneously given as that of the inversion of the row form. Also, he continues to use only one numbering system. The numbers 1-12 are used for all forms with no corresponding numbering system being set up for the retrograde forms. For the purposes of this article Halffter's hexachord labeling will remain because it does. not affect the structural analysis.

Example 13: Composer's chart of prime and retrograde forms of "Serie A" of Escolio.

In exploring the harmonic-tonal treatment of Escolio several aspects seem important. For example:

1) Halffter often uses repeated phrases or "reflected images" as he called them in his 12-tone works. 17 This compositional technique allows the listener time in which to absorb the new information that is being heard. Sometimes the "reflected image" is a literal repeat and sometimes it contains a slight variation. In Escolio the only instance of the "reflected image" not being a slight variation occurs in measures 162-164 with its answering component in measures 165-167 in an inversion format.

2) The opening anacrusic motive E ![]() -D-E

-D-E ![]() , which has already been commented upon elsewhere, has a parallel motive, ascending stepwise, F#-G#-A (ms.8-9). Variations on these two motivic ideas may be seen in such examples as: ms. 1213, ms. 20-21ms. 22-23; ms. 28-29; ms.32-33 (left hand in disjunct descending order, B

, which has already been commented upon elsewhere, has a parallel motive, ascending stepwise, F#-G#-A (ms.8-9). Variations on these two motivic ideas may be seen in such examples as: ms. 1213, ms. 20-21ms. 22-23; ms. 28-29; ms.32-33 (left hand in disjunct descending order, B![]() -A-A

-A-A![]() ), ms. 36, ms. 38- 39, ms. 48, etc. In the "B" section (ms. 64105) the descending E6-D motive of the opening of the piece is replaced by an ascending motive of C#-D and its descending counterpart C#-B (ms. 65). Corresponding examples are found in ms. 72-73, and ms. 75.

), ms. 36, ms. 38- 39, ms. 48, etc. In the "B" section (ms. 64105) the descending E6-D motive of the opening of the piece is replaced by an ascending motive of C#-D and its descending counterpart C#-B (ms. 65). Corresponding examples are found in ms. 72-73, and ms. 75.

3) The corresponding accompaniment to the above melodic motives E ![]() -D-E

-D-E ![]() and F#-G#-A# must also be examined. In ms. 1 there appears to be two harmonic juxtapositions - the dyad E

and F#-G#-A# must also be examined. In ms. 1 there appears to be two harmonic juxtapositions - the dyad E ![]() -G against the resultant trichord B-F#-A# - which give a tonal ambiguity. This trichord corresponds to a transposed example found on page 14 of the "Conjunto de Series".

-G against the resultant trichord B-F#-A# - which give a tonal ambiguity. This trichord corresponds to a transposed example found on page 14 of the "Conjunto de Series".

Example 14: Trichord derived from G minor chord (Numbers 6, 4, 3) of the Inversion of the Hexachord on p. 14 of the "Conjunto de Series" using formula 3-52, 3+5+, 5-52.

In ms. 9 the accompaniment consists of a descending 7th C#-E-C, which is the same chord in the "Conjunto de Series" found on page 12 (Example 10a), but in transposition. Similar chords occur in ms. 13 and ms.73. In the appearance of both motives, as the motive descends, the accompaniment ascends and vice versa.

4) In ms. 3 there appears to be a G# minor chord in 1st inversion with an upper appogiatura of A# and auxiliary note of F#, which could be interpreted as the bitonal combination of G# against F#, each tone having the half-step relationship to the 1st note of Series A.

5) In ms. 12 the 7th chord F#-C#-E is similar to the chord found in series on page 24 in the "Conjunto de Series" (Example 15). This trichord appears in its transposed form in ms. 29, ms. 53, ms. 72, etc.

Example 15: Trichord derived from F major chord (Numbers 5, 6, 2) of the 1st hexachord on page 24 of the "Conjunto de Series" using the formula 1-52, 3+52, 3+5.

The F# in ms. 12 becomes a pivot tone for the trichord found in ms. 13 F#-D-F (Example 16) and occurs in transpositions in ms. 49 with its inversion, in a slightly altered form in ms. 53, ms. 146, and ms: 149 (broken form).

Example 16: Trichord derived from D minor chord from the first hexachord (Numbers 5, 6, 2) of the series on page 18 of the "Conjunto de Series" using the formula 1-5+, 1-52, 3+5+.

The trichord A ![]() -E

-E ![]() -G in ms. 39 corresponds to an example from page 18 of the "Conjunto de Series". and is transposed in ms. 85, etc. (Example 17)

-G in ms. 39 corresponds to an example from page 18 of the "Conjunto de Series". and is transposed in ms. 85, etc. (Example 17)

Example 17: from F major triad of inversion of the 1st hexachord (Numbers 6, 5, 2) of the series on page 18 of the "Conjunto de Series" using the formula 1+5+, 5-5+, 5+5+.

The Stravinsky-like motive of ms. 97-99 is derived from elements found in ms. 1, ms. 23, ms. 70, etc. undergoing transformations from harmonic to melodic usage.

6) In ms. 30 the trichord D-F-C# is the transposed version of the chord derived from notes 4-5-6 of the series found on page 12 of the "Conjunto de Series" (see Example 10a).

7) Blatent bi-tonal combinations occur in ms. 36-40 of F major against A 6 M7 and possibly in ms. 39 and ms. 53 of A ![]() M7 against C major. In ms. 45 C augmented appears against C minor. In ms. 57 C major is pitted against an implied B which becomes B

M7 against C major. In ms. 45 C augmented appears against C minor. In ms. 57 C major is pitted against an implied B which becomes B![]() m7 in the next measure. In ms. 85 C major occurs against its -resonances of the trichord B-F#-A#. The continuing B-C conflict is featured in Poulencian fashion against a D

m7 in the next measure. In ms. 85 C major occurs against its -resonances of the trichord B-F#-A#. The continuing B-C conflict is featured in Poulencian fashion against a D ![]() major triad in ms. 187-197 as in the "Perpetuum Mobile," or 'Homenaje a Poulenc," or in Halffter's

Apantes para Piano 1936-1982. (Poulenc was a mutual friend of de Falla and Halffter.) The same D

major triad in ms. 187-197 as in the "Perpetuum Mobile," or 'Homenaje a Poulenc," or in Halffter's

Apantes para Piano 1936-1982. (Poulenc was a mutual friend of de Falla and Halffter.) The same D![]() major triad becomes the antagonist against D major in ms. 198-199. In ms. 201 the chord CD#-F#-B is placed against a B

major triad becomes the antagonist against D major in ms. 198-199. In ms. 201 the chord CD#-F#-B is placed against a B ![]() major triad quickly followed by D-C#-B

major triad quickly followed by D-C#-B ![]() -A-G#-G.

-A-G#-G.

8) Distinctive harmonies include an F7 or V7 of B 6 in ms. 71 against C; possibly B ![]() 7 or v7 of E in ms. 75; D7 or V7 of G in ms. 165; and half-diminshed chords in ms. 65 and 162; a minor-major 7th in ms. 185. Finally, at least one ambiguous

trichord becomes clarified in ms. 195-196 when all four notes of the chord appear creating the chord C-D#-F#-B - the ending chord of the piece. The outer notes of this chord appear in inverted guise in ms. 201.

7 or v7 of E in ms. 75; D7 or V7 of G in ms. 165; and half-diminshed chords in ms. 65 and 162; a minor-major 7th in ms. 185. Finally, at least one ambiguous

trichord becomes clarified in ms. 195-196 when all four notes of the chord appear creating the chord C-D#-F#-B - the ending chord of the piece. The outer notes of this chord appear in inverted guise in ms. 201.

9) In the Recapitulation the following may be found: ms.106-141= literal repeat; ms. 142 goes towards C#-D# instead of the C-A ![]() with implicit E

with implicit E![]() -E conflict of ms. 39 and arrives at ms. 144 with the trichords of G-D#-F# against B-D-B

-E conflict of ms. 39 and arrives at ms. 144 with the trichords of G-D#-F# against B-D-B![]() . The trichord of F-A

. The trichord of F-A ![]() -E against C#-A-C in ms. 149 is

much stronger than its counterpart in the exposition in ms. 44, indicating harmonic tension and building to climax. In the exposition in ms. 44, indicating harmonic tension and building to climax. Ir ms. 150 the trichords of G-D#-F# against B-D-13 6 continue the tension.

This appears to be the first time Halffter uses the motive of the "B" theme with

the Series A in ms. 154 is indeed erroneous upon further examination, as the E 6 (D#,' of the initial theme occurs in the preceding measure to make an unusual presentation of the E

-E against C#-A-C in ms. 149 is

much stronger than its counterpart in the exposition in ms. 44, indicating harmonic tension and building to climax. In the exposition in ms. 44, indicating harmonic tension and building to climax. Ir ms. 150 the trichords of G-D#-F# against B-D-13 6 continue the tension.

This appears to be the first time Halffter uses the motive of the "B" theme with

the Series A in ms. 154 is indeed erroneous upon further examination, as the E 6 (D#,' of the initial theme occurs in the preceding measure to make an unusual presentation of the E![]() -D-E

-D-E![]() motive. When the "B" section does return it is ir much abbreviated form (ms. 161-172) and only to be annulled by conflicting tonalities such as in ms.163-164 and ms. 166-167. A transitory motive is

found in ms. 167-168, originally from the "A" section (ms.23-24) but appearing in altered form in the "B" section for the first time in ms. 70 (Exposition).

motive. When the "B" section does return it is ir much abbreviated form (ms. 161-172) and only to be annulled by conflicting tonalities such as in ms.163-164 and ms. 166-167. A transitory motive is

found in ms. 167-168, originally from the "A" section (ms.23-24) but appearing in altered form in the "B" section for the first time in ms. 70 (Exposition).

10) The biggest surprise of all is the fundamental of the piece, D, and a series oi ascending resonant 7ths - C#-C-B-B ![]() -A-G#-G constructed upon it, which leads to the conclusion that the ending note G is really the beginning note and the relationship between the two is one of tonic-dominant. These notes are never revealed in their direct form until the end (ms. 202-205). In their inverted form they obviously form a series of half-step dyads nicely associated with the opening theme of the piece. The superpositions of 7ths is characteristic of Halffter from his early years (Example 18.) 18

-A-G#-G constructed upon it, which leads to the conclusion that the ending note G is really the beginning note and the relationship between the two is one of tonic-dominant. These notes are never revealed in their direct form until the end (ms. 202-205). In their inverted form they obviously form a series of half-step dyads nicely associated with the opening theme of the piece. The superpositions of 7ths is characteristic of Halffter from his early years (Example 18.) 18

Example 18: Generator Chord of Escolio mm. 202 - 205.

11) Structurally, Halffter's allusions to Stravinsky and Poulenc are situated in a similar place in Escolio as de Falla's quotation from Debussy's "La Soiree dans Granade" from Estampes in the next-to-last phrase of Homenaje a Debussy (m m. 63-66.)

Summary and Conclusion:

In summarizing the techniques between de Falla and Halffter's dodecaphonic style as exemplified in Escolio it can be seen that a great similarity exists.

1) Halffter has consciously striven to uphold the de Falla aesthetic even while using dodecaphony. Especially obvious is Halffter's use of the harmonic juxtapositions derived from the generator - resonance concept of the Superpositions or "apparent poly-tonality."

2) Maintaining the ornamental elements of cante jondo (literally "deep song" of the flamenco singers) in 12-tone language, such as the appogiaturas and to a lesser extent, the trill, is also achieved.

3) The most distinct difference found in the evolution of the de Falla aesthetic is in melodic treatment. As has been mentioned, de Falla is faithful to the folksong, using it in a pure and yet original way, sometimes in canon at the second or other intervals. Halffter's use of melody is more neo-classic in nature. While de Falla generally does not develop melody as such, Halffter's technique employs repeated phrase statements called "reflected images." This is for the listener's benefit, due to the lack of tonality. For de Falla, the interval of the minor second had mystical connotations; for Halffter the interval with its corresponding inversion of the 7th opened other harmonic worlds and destroyed tonality. De Falla's use of the canon at the various intervals can be compared to the hexachordal transpositions by Halffter.

4) De Falla pays tribute to colleagues; in a subtle way, such as in his neo-Baroque (or to use de Falla's words "pre-classical"19) Concerto by complex rhythmical treatment (Stravinsky and Bartók) or by the use of the harpsichord and "internal rhythm (J.S. Bach and Domenico Scarlatti) or by the lack of melodic development (Stravinsky). Halffter, throughout all of Escolio, is paying tribute to both mentors: Manuel de Falla and Arnold Schoenberg and his friends Francis Poulenc and Igor Stravinsky.

5) A clear and transparent texture continued to be an ideal of the neo-classic school and of Halffter in all his works with no excess of compositional materials used. De Falla too uses an economy of musical means to achieve his objectives, even while juxtaposing or condensing various themes.

It seems clear that Rodolfo Halffter did indeed carry on the tradition of of Falla's "apparent polytonality" and aesthetic ideal in a unique way. With the main components of rhythm, texture, ornaments, and harmony, Halffter has managed to create a 12-tone language remarkably like the ideals of de Falla and the other Gongorists. Only in the "melodic" or hexachordal usage is there a convergence between Halffter and de Falla. While liberties within the twelve-tone system began almost as soon as it was invented (as seen in the works of Alban Berg and even Schoenberg himself in the Ode to Napeleon Buonaparte, op. 41), the concept of "poly-tonality" within the tone row is more rare. Such examples may be found in several of Halffter's works when he uses a double series - or when he manipulates the single series to include potential bi-tonal combinations, such as was observed in Escolio. Other examples of poly-tonal usage in the 12-tone method may be found in the works of yet another Schoenberg student, the Greek composer Nikos Skalkottas; but that is the subject of yet another article.

In a speech at the Juan March Foundation commemorating his eightieth birthday, Halffter explained:

It is not important which sonorous materials I have used in the different stages of my career, nor the mutations that my musical languages have undergone. It is certain that I have never departed from the neo-classical aesthetic belief. For this reason, my evolution presents an evident internal cohesion .... My ascription to dodecaphony is the result of a long evolution. My dodecaphonic music is very similar. Practiced with liberty, without scholastic strictness, which...well conserves those incriminating characteristics of my transparent texture and an extreme condensation of sonorous material; qualities all of which are characteristic of the music of (de) Falla and his followers.

20The spiritual link between Rodolfo Halffter and Manuel de Falla remained. Halffter, like the superstitious de Falla, died just a few weeks before completing his next birthday. Had he lived longer, Halffier might have continued to develop de Falla's aesthetic ideal using Mexican elements as a basis, something he achieved in his last work Paquilitzli. But that is also another study. Students of Halffter, especially Mario Lavista of Mexico, are carrying on the de Falla tradition. And if one day Halffter's unedited papers are published, they will shed more light on the complexity of "Don Manuel's" mind.

Constructing an imaginary situation, Halffter continued in his Juan March speech,

If (de) Falla were alive and could hear my dodecaphonic works, I am sure that he would be scandalized. He, who believed in the eternal law of tonality, would have refused to admit that there was a certainty of the collapse of tonality. I would have tried to explain to him that my adherence to the twelve-tone system did not represent a substantial change of aesthethic position nor of musical idealogy and that I continued being one of his most faithful servants...."

21

Notes:

1 See Harper 1985:3.

2 Iglesias 1979:78n.

3 Harper 1983:2.

4 Mayer-Serral 943:10. In Granada in April of 1928 Halffter received some counsels from the tight-lipped de Falla, who was more interested in giving alms to the poor than in teaching. "...we analized [sic], among other pieces, various sonatas of Domenico Scarlatti. (De) Falla's admiration for Scarlatti had no bounds. He admired the freshness of his inspiration and above all, the rhythmical asymmetry of his phrases and periods. Moreover, (de) Falla made me hear the distant rumblings of guitars and popular Spanish songs which emanated, like exquisite perfume, from these sonatas...." (Harper op.cft:4) Included among these sonatas were Longo 15 in a minor and Longo 58 in d minor. (Harper 1983:1)

5 Lucas 1854:43-45, Shirlaw 1960:18.

6 The four- page document, Superposiciones, was published in November of 1975 by Carlos Lecea with the authorization of de Falla's only surviving heir Maria de Isabel de Falla de Garcia de Paredes as an early centenary tribute to the composer. It is the only written testament to date which clearly shows how de Falla developed his ideas of "apparent polytonality." Found amongst de Falla's papers after his death, and in the composer's hand, the document can be divided into two categories: 1) the first two pages contain numbers, mathematical calculations, and chords; 2) the last two pages are specific examples and sketches taken from de Falla's own works. (See Appendix IV).

While it is not known exactly when nor why the Superposiciones came into being, it is conjectured that de Falla might have written these from memory for the use of his students because of the few errors or repetitions they contain. (Gallegol990:157) As there are no examples from the Concerto, Rodolfo Halffter speculated that they were formulated probably around 1922-23. (Halffter N/D: Notes) The author is indebted to Rodolfo Halffter for the precious gift of the limited edition of the Superposiciones and his unpublished commentaries o them as well as his unpublished analyses of Don Lindo de Almeíra and Tres Hojas de Album.

For de Falla, who remained faithful to the tonal system with a kind of religious fervor, the generator- resonance concept created an enormously rich harmonic palette from which to draw inspiration. Halffter, who was first given photocopies of the unpublished Superposiciones (See Appendix VI), also conjectured that they are not complete and are merely examples of the myriad possibilities which can exist. (Iglesias 991:299) Indeed this is true, of much of the sketch material housed at the Manuel de Falla Archives in Granada contains many other examples of superpositions from other works not listed in the Superposiciones, such as the Concerto, Psyché, El Teatro del mundo,

and others. Whether or not the document Superposiciones forms the basis for a "theory of resonance" for de Falla is speculative and not within the realm of this article; but certainly a harmonic base such as found in, Hindemith's system does not seem to exist,7 Although de Falla heard folksongs from the crib, his interest in them was heightened by his studies with the great musicologist-folklorist Felipe Pedrell begun n 1901. And with the dedication of the Gongorists to renovating the Spanish artistic language, what greater source could be found than in the native songs and dances of Spain with its rich multi-cultural heritage. De Falla's fascination with the cante jondo ("deep song") of the Romeny people (gypsies) led him to organized a competition in Granada in 1922 for the best authentic portrayal of native chanting. The cantejondo influence is heard over and over in de Falla's works in the accaciaturas, the nasqueado (strumming) of the guitar, the modulations, the melodic inflections, even in his late and more abstract works. And along with the micro-tonal chanting of the cantejondo, de Falla was enchanted with the scales from other cultures (such as Moroccan scales found in an undated article in Le Courier Musical amongst de Falla's papers) , also advocated by Louis Lucas.

De Falla was obsessed by finding authentic melodic sources and often would stop to write down the song of an old woman in the street or ask a Gypsy to sing and dance a particular "genre." In his Siete Canciones Populares Españolas (Seven Popular Spanish Songs) de Falla draws on sources from old Cancioneros (songbooks), sometimes juxtaposing several songs together to form a coherent work.

Interesting too is the fact that De Falla's first career inclination was literary, not musical, which might explain his predilection for literary sources as a musical basis for his compositions.

8 While the date of this unpublished document is unknown, it was probably after Halffter received the "Superposiciones" papers in 1971. The use of the 7th chord is predominant in Halffter's works, the 7th chord being a prominent characteristic of the Concerto, a work highly revered by de Falla's admirers and considered to be the apex of all his works until his last, Atlantida.

9 Halffter said that Schoenberg never spoke of his own compositions, but drew upon those of the masters in order to illustrate his ideas. In the Minuet of the first piano sonata of Beethoven, Schoenberg pointed out that the four forms of dodecphonic treatment exist (Example 8.)

10 Halffters student, Jorge GonzaIez Avila, actually premiered the first 12-tone piece in Mexico in Mexico City in 1952. However, since Halffter taught and developed the system in his own unique way, publishing many dodecaphonic works from 1953 onwards, he is considered today to be Mexico's first 12-tone composer.

11 Iglesias 1979:195 and translated by the author in Harper 1985:25.

12 During work on a doctoral thesis entitled The Piano Sonatas of Rodolfo Halfftar Transformation or New Techniques? the author compiled a vector analysis of various elements used by de Falla in order to compare them with Halffter's 12-tone usage. Some of the chord conglomorates analyzed were: the chord derived from the guitar strings, from the overtone series with the fundamental note of C (partials 2-7); the opening chords of the Concerto by de Falla; Halffter's first published piece (Naturaleza Muelta) not yet under the influence of de Falla; and several chords from Haffter's various sonatas. By that time (1985) Halffter had completed most of his works. He was pleased with the vector analyses, but made very little comment nor mentioned the existence of the "Conjunto de Series." However, it seems unlikely that Halffter would have written the document after having composed nearly his entire opus. He was a very precise and meticulous person, as his German name might imply. Even the pencils on his desk were sharpened ready for use. The author is indebted to Halffters widow for the gift of the unpublished "Conjunto de Series" in 1993 and to the late composer himself for his row analysis of Escolio.

13 Halffter: Conjunto de Series, Introduction, translation by author.

14 Pede 1981:6.

15 Velcizquez 1974:309.

16 "0" refers to traspositions of the original form of the series with different trasposition levels indicated by the subsequent letter ("a," "b," "c," "d," etc. see Example 13 from Halffter's row charts). "I" (see Example 13 below) refers to the inversion and "IR" to the retrograde inversion.

17 Harper 1983:2.

18 There may or may not be significance to the fact that Halffter constructed a series of seven sevenths to achieve this tonic-dominant relationship. However, it is widely known that de Falla was highly superstitious, feeling that his life fell into seven year periods and that he would not live to see his seventieth birthday (which he didn't!) How significant, then, is the fact that de Falla's Homenaje a Debussy contains seventy measures (7 times 10)?

19 Cited in Romantyzm w Muzuce (Poland: 'Muzyka', [1928] p. 140, translated by Alan Lem in "Manuel de Falla on Romanticism: Incites into an uncited text" by Michael Christoforidis in Context 6 (Summer 1993-94) p.26.

20 Harper 1985:36.

21 lbid

Appendix I: Composer's Unpublished Row Designations of Escolio

Appendix II: "Conjunto de Serie" (without inversion)

Appendix III: de Falla's Superposiciones Reduced to Conjunct Forms with Pc Set Numberings

Appendix IV: List of Musical Examples from Pages 3 and 4 of the Superposiciones

Appendix V: Introduction to Conjunto de Series (English translation by author)

Appendix VI: "Afternoon Retreat in Granada"

ex tempore

as published in Vol. VIII/1, Summer 1996