Varèse's Hyperprism and Penderecki's Polymorphia

Christopher

Meister

This paper concerns itself with comparing two different pieces of

twentieth-century music as self-contained and internally-referent information

structures. To that end, the following questions will be addressed: how does

one part of a piece compare with another; where are the significant

compositional similarities, and in what ways do these similarities fashion

themselves into larger structures and organizational patterns? The pieces to be

examined are Hyperprism, by Varèse, and Penderecki's Polymorphia;

Hyperprism will be discussed first, then Polymorphia, and as the

latter is analyzed such comparisons will be made between the two as seem

pertinent.

The Varèse contains a large percussion

complement, and the present analysis concerns itself with the pitched

instruments only. In order to examine briefly their harmonic content, this

paper borrows from Larry Stempel's 1979 Musical Quarterly article

"Varèse's 'Awkwardness' and the 'Symmetry in the Frame of Twelve

Tones'". According to Stempel, much of Hyperprism's harmonic

structure may be explained as one kind or other of chromatic segment. The

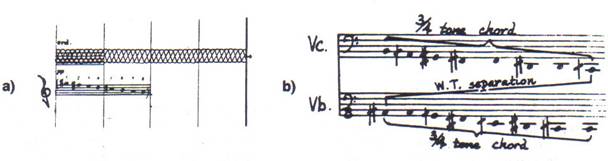

simplest and least ordered of these segments are shown in Examples 1a and b.

Example 1a and b: Varèse, Hyperprism, chromatic segments

(c) 1924 by G. Ricordi

& C.; Copyright renewed. Reprinted by permission of Hendon Music, Inc.

Within the overall category of chromatic segments, special treatment

appears to have been reserved for chromatic trichords whose middle pitches have

been displaced either up or down an octave (see Examples 2 a-e). Frequently,

"up" and "down" displaced trichords will be played off

against each other. Notice that this "updown" play creates a [1] loose sort of symmetry.

Example 2a through e: Varèse, Hyperprism, chromatic segments

(c) 1924 by G. Ricordi & C.; Copyright renewed. Reprinted by

permission of Hendon Music, Inc.

Despite the considerable gains towards understanding

Hyperprism that this harmonic analysis offers, it fails to address the

matter of the composition's non-amplitudinal "dynamics." The

remainder of this paper's first half sketches out a model of Hyperprism's

behavior, which might be expanded to include Stempel's pitch work. This model

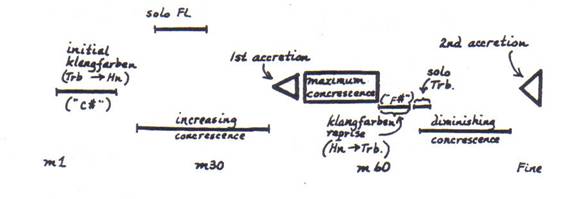

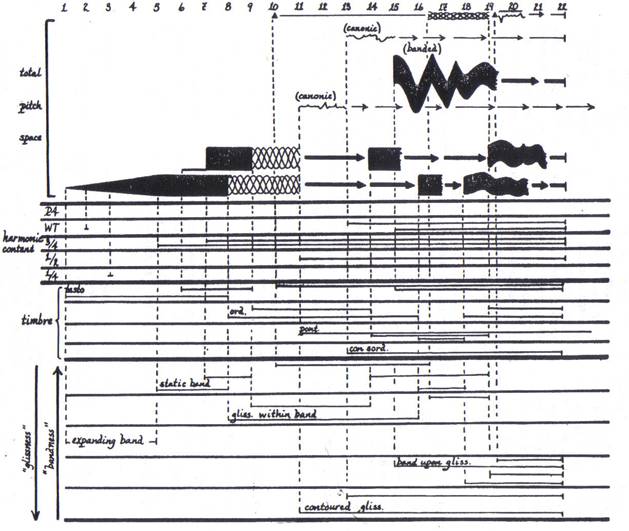

divides Hyperprism's musical activity into five

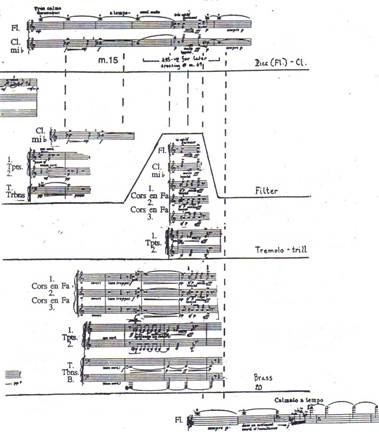

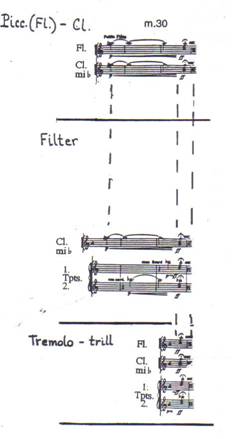

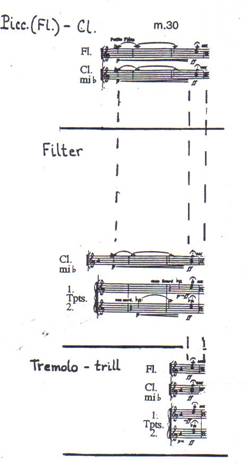

"eventcategories." (Example 3a. In this and similar examples,

temporal alignment is represented vertically, and measure numbers appear above

the topmost staff.) The five categories are 1) piccolo (flute)/clarinet, 2)

filter, 3) tremolo/trill, 4) brass, and 5) solo. Each of these events cuts in

and out of the sonic collage fairly independently of the others. Although

Varèse is not particularly meticulous about an appearance's taking up

the exact musical gesture that its previous disappearance had left off, the

continuity is nevertheless obvious, and each event has its own [2] formal-dramatic pattern of behavior.

Example 3a: Varèse, Hyperprism, mm. 1-20 Event Relationships

b) c)

Example 3b and c: Varèse, Hyperprism, Example 3c:

Varèse, Hyperprism, mm. 28-30, mm. 47 -48. Exploration of New

Relationships Maximum Concrescence

(c) 1924 by G. Ricordi & C.; Copyright renewed. Reprinted by

permission of Hendon Music, Inc.

The event-categories, however, do not behave in

solely independent fashion: their primarily linear progressions are to some

extent influenced by an interactive inclusional association among them, whereby

a musical moment will appear simultaneously in more than one category (see

example 3a, in which dashed lines indicate this inclusional associativity).

This occurs when a section of the music contains enough traits of two (or more)

categories to be included in both. The ramifications of this multiplicity of a

gesture's interpretation are most profound near Hyperprism's beginning,

for it is here that a single event, the filtered one, generates most of the

other categories: for instance, the filter event in measure 4 begets first a

constituent of the brass event, then in measure 6 the tremolo event, and later

the piccolo/clarinet event in measure 14. The piccolo/clarinet event, which is

itself a second-generation gesture, fathers the initial solo event, which

begins in measure 18. Following this initial generation of material, the music

explores new associations among the event-categories. For instance, the tremolo

of measure 17 may be described as the brass gesture below and the

piccolo/clarinet gesture above finding a new way of relating to each other. (So

far the brass and piccolo/clarinet categories have found common ground through

only the filter event at measure 14, not through the tremolo/trill).[3]

A further example of Hyperprism's

concrescence may be seen in Example 3b measures 28-30, during which three

separate events converge into one.This begins with the piccolo/clarinet event

meta-morphosing into a filter event with the addition - on the clarinet pitch

concert B-flat - of first a muted trumpet in measure 29, and later a non-muted

trumpet in measure 30. This entire sonority (piccolo, piccolo clarinet, two

trumpets) remains on the same pitches, but transforms itself into a tremolo

event at the fermata of measure 30: all three categories, the filter, the

piccolo/clarinet, and the tremolo, have at this point converged into a single

gesture. The most extreme instances of interrelation among the categories are

those at measures 47-48 (Example 3c) and an identical but longer passage at

measures 56-59; it is here that gestures belonging to the piccolo/clarinet,

filter, and brass events achieve an extraordinary level of concrescence. This

happens in that together they create the impression of a single, animated

texture, and each of the categories' gestures co-exists with the others in a

state of near-equivalence. All of the gestures share enough similar traits to

be included within the tremolo/trill category in example 3c. But, curiously,

the dissipation of these categorical characteristics throughout the texture at

these two moments of maximum convergence appears to have concomitantly induced

an exhaustion of the will to concrescence, for after these two moments of

maximum convergence the number and level of interrelationships drop abruptly.

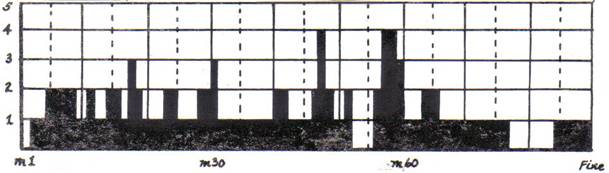

(See figure 1 which is a graph of the form of Hyperprism and figure 2

which is a graph of the number of associations per convergence.)

This model of inclusional convergences contains a

place in it for the augmented triad begun by the horns in measure 15. This is

an awkward harmonic gesture to explain, in that it does not fit well into the predominantly

chromatic-segment harmony. However, if harmony is considered to exist within Hyperprism's

inclusionallyassociative fabric, one might argue that this augmented triad's

abruptness is buffered by the ensuing trumpet entrance in measure 16. This occurs

in that the trumpets play only one major third, half as many as the horns, and

they also repeat their interval, repetition being one of the brass event's

characteristics. This presentation of the trumpets' major third (enharmonically

spelled as a diminished fourth) more closely approaches Hyperprism's

compositional norms than did the horns' augmented triad: even a disparate [4] harmonic undercurrent is absorbed into the

mainstream of the compositional flow.

Figure 1: Varèse, Hyperprism,

Form

Figure 2: Varèse,

Hyperprism, Event-categories incorporated per convergence

a) b)

b)

Example 4: Polymorphia, Mono-intervallic and Symmetrical Pitch Formations:

a: no. 24, Quarter-Tones. b: no. 31, Half-Steps. c: no. 7, Three-Quarter-Tones.

d: Whole-Tones. e: no. 27, Perfect Fourths

(c) Penderecki POLYMORPHIA (c) 1963 by Herman Moeck Verlag, Celle. (c)

Renewed. All Rights Reserved Used by permission of European American

Distributors Corp., sole U.S.

and Canadian agent for Herman Moeck Verlag, Celle.

Example 5: Polymorphia, Symmetrical Non-Mono-Intervallic Pitch Formations. a:

no.59, b; no.7

(c) Penderecki POLYMORPHIA (c) 1963 by Herman Moeck Verlag, Celle. (c)

Renewed. All Rights Reserved. Used by permission of European American Distributors

Corp., sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Herman Moeck Verlag, Celle.

Example 6: Polymorphia. a: no. 37, b: no.

59, c: no. 60, d: no. 67. Polymorphia's Only

Non-Symmetrical Pitch Formations

(c) Penderecki

POLYMORPHIA (c) 1963 by Herman Moeck Verlag,

Celle (c) Renewed. All Rights Reserved Used by permission of European American

Distributors Corp. sole U.S. and Canadian

agent for Herman Moeck Verlag, Celle.

To sum up the discussion so far: Hyperprism operates

as a collage of musical gestures belonging within one or more behavioral

categories. Judging from the concrescionally-depletional effect that the two

areas of maximum convergence created for the remainder of the piece, it seems

reasonable to hypothesize that any gestural confluence - a musical moment's

belonging to more than one category at a time - may have some sort of lesser

and more localized impact upon the course of the music. In Hyperprism Varèse

pared the function of harmony in order to imbue the non-pitch elements of

timbre and articulation with an increased precedence in the compositional

organization. Polymorphia exhibits the same emphasis of timbre and

articulation at the expense of traditionally pitch-oriented compositional

processes. However, there exist significant differences between the two pieces'

material and organization. For instance, Hyperprism's occasional

employment of "up-down chromatic [5] trichords" are its sole display of near-symmetrical chord

structures. By contrast, Polymorphia's chord forms are virtually all

symmetrical, some mono-intervallic (Example 4), some not (Example 5). Very few

exhibit no symmetry (Example 6). In addition, Polymorphia's harmonic

structures are drawn from a wider intervallic field than [6] Hyperprism's (see Examples 4

- 6).

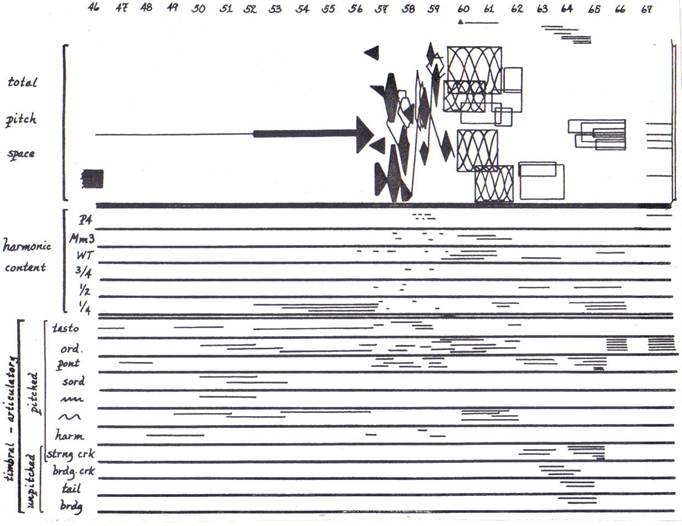

But Polymorphia's proliferation of

intervallic structures is only one facet of its compositional network, in which

the harmonies are treated as detachable entities to be mapped onto other,

likewise detachable and mappable articulations, timbres, and shapes. For

instance, a fair amount of information is exchanged just among shapes alone:

the bottom of figure 3 presents two prime shapes, "band" and

"glissando," and all the other shapes in this section (glissando

within a band, expanding band, and band upon glissando) are built from these

two prime shapes. The top of Figure 3 is a simplified graph of where these

shapes occur in the total pitch-space and when in time. And the middle portions

of Figure 3 tell what timbres and intervallic structures are present at what

time.

Figure 3: Polymorphia., graphic reduction of no.s 1-22

Besides considering these shapes to exist within a

"bandness" or "glissness" scale, one might also view some

of them as generating others through a mapping process: for instance, the

static band at number 5, if mapped onto the shaped glissandi at numbers 11 or

13, yields the banded glissandi at numbers 15, 18, and 19. This mapping works

in a small way within the shape field (or parameter), but if one were to take

the mapping procedure outside of any one particular parameter and apply it

between the two parameters of shape and intervallic content - to cite but one

example - the mapping applications begin multiplying themselves. For instance,

an interval may be cross-mapped from one shape to another; note that the

canonic glissando at number 13 and the banded glissando at number 15 both share

a whole-tone harmonic structure. [7] Conversely, one shape may have more than one chord-form mapped onto

it.And when timbre enters into the picture, the mapping possibilities begin

multiplying quite [8] rapidly.

This appears to be a case of freer employment of a

wider field of harmonic, timbral, articulatory, and even shape material than

was found in the Varèse. In Hyperprism, despite any

transformations created by the inclusional associativity, one could rightly

speak of the "identity" of an event-category being maintained

throughout, largely due to the narrower field of material and the more

linearly-invariant mapping associations; but in the Penderecki, the personality

metaphor seems inappropriate: instead, parametric phenomena "glom on"

to each other, creating global units - bands and glissandi - recognizable in

their macro-structure, but complicated to the point of being bewildering in

their compositional interrelationships. Before proceeding to the remainder of Polymorphia,

a few comments regarding #'s 1-22 are in order. First notice that all of the

sounds are long, bowed ones: none are short. Second, all are pitched, either

definitely or indefinitely. Third, within the field of intervals, all are used

with the exception of the quarter-tone, major and minor thirds and perfect

fourths. And finally, from the beginning to #22 more and more sounds are piled

on.

Significantly, from #'s 22-44 this whole situation

reverses itself (Figure 4). First, all the sounds are short ones, save those

few briefly hanging over from the previous section; second, from #'s 22-38 the

perfect fourth and quarter-tone, two intervals virtually ignored in the first

section, play a major role; and third, unpitched tones are introduced alongside

the pitched tones for the first time, thus creating a pitched-versus-unpitched

argument which extends from #'s 22-44. Even though this whole section in figure

4 is limited to only short sounds, much of its interest is the result of the

course of this pitched-unpitched argument: from #'s 31 to 37 the pitched side

of the argument gains ground, to the point of eventually saturating both

pitch-space and intervallic content between #'s 37 and 38. (See Example 6a.)

But afterwards, from #'s 38-88, only the unpitched sounds are used, these

becoming increasingly removed from pitched territory, to the point of not being

produced on the instrument at all.

Figure 4: Polymorphia., graphic reduction of no.s 46-67

Another facet of Figure 4 which bears discussion is

the existence within it of two successive accretions; the first is the

pitchedunpitched argument from #'s 22 to 38, which collapses, making way for the

second, totally unpitched accretion from #'s 38-44. Similarly, the initial

section, #'s 1-22 of figure 3, may also be considered an [9] accretion and

subsequent collapse. Since each of these large-scale accretions is built from

its own set of musical characteristics, it becomes clear that a very few

compositional operatives define the conditions for a considerable stretch of

music. Were one to compare Penderecki's accretions with those in the

Varèse, he would find that in Polymorphia, they occur for minutes

at a time and are the main sections of the piece, whereas in Hyperprism

the accretions appear to function as signposts of the [10] larger sections, analogous to codetta and coda of

sonata form.

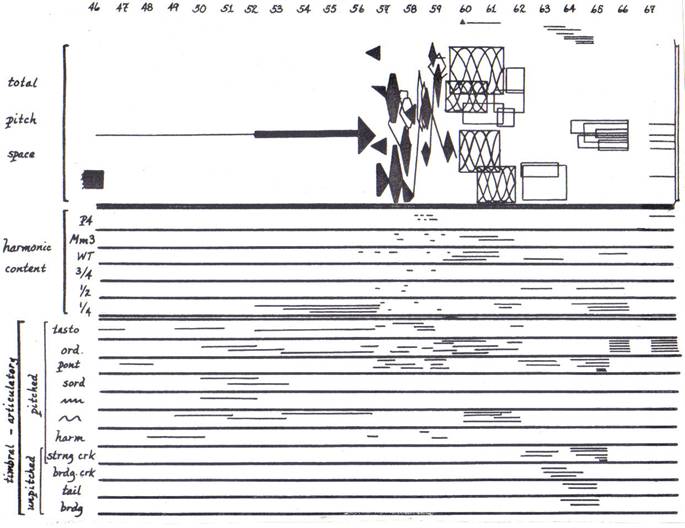

This last parenthetical remark raises the question

of form in Polymorphia. Examination of the "articulatory"

section of figure 5 shows that all the sounds from #46 to the end are long

ones, as they were between #'s 1-22. Additionally, timbres, shapes, bands, and

glissandi similar to those of figure 3 are developed throughout in figure 5;

from this it seems safe to infer that Polymorphia's form is essentially

an ABA in its large-scale outlines.

But besides being a recapitulation of Figure 3,

Figure 5 is also a summation of the previous discourse. Note that the intervallic

content of Figure 5 incorporates each of the two previous sections' sets of

intervals in addition to adding some intervals of its own: clearly, the entire

harmonic content of the piece is being summed up right here. And besides

functioning as a harmonic summation, this third section additionally

incorporates the long-versus-short and pitched-versus-unpitched arguments of

the two preceding sections.

Figure 5: Polymorphia., graphic reduction of no.s 46-67, bridge pitched

and unpitched sounds.

This incorporation, or "synthetic" phrase,

takes place near the very end of Polymorphia in the following manner:

first, note in the lower half of the timbralarticulatory portion of figure 5,

that at #63 the instruments begin playing a behind-the-bridge "ugly

creaking" (Penderecki's term). This sound is a continuous series of short,

individual "creakettes," and as such this unpitched sound

incorporates for the first time both the long and short articulatory

antitheses. Immediately after beginning this behind-the-bridge creaking, the

performers are directed to play on the tailpiece and on the bridge itself, thus

producing the first truly long, unpitched sound: the pitched-unpitched,

long-short events are being mapped onto each other in new combinations. And these

new mappings find their most inclusive expression in the creaking bands begun

at #62: these incorporate both long and short sounds as did the

behind-thebridge creaking; and since their inharmonic (unpitched) content

partially obscures the tones' pitches, these quasi-pitched, creaking bands

additionally bridge pitched and unpitched sounds.

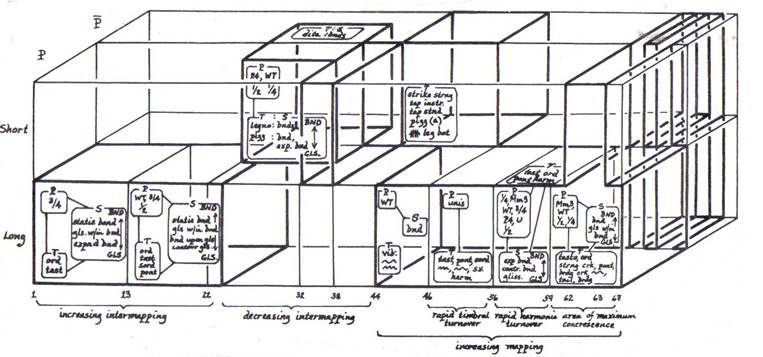

Examination of Figure 6, a three-dimensional model

of information exchange in Polymorphia, provides an overall sense of how

information functions throughout the piece. To explain the model briefly: time

runs from left to right, and rehearsal numbers are placed below the X-axis; the

Y-axis is divided into "long" and "short" halves; and the

receding Z-axis is divided into pitched and unpitched halves, the unpitched

portion being denoted by a "P" with a line above it. The heavy lines

show when and to what degree the music is in which of the available quadrants;

and the remarks interior to each of the heavy-line "large-operative"

boxes show the field of mappings within each box among the parameters of pitch,

timbre, and shape: a line between two parameters means that most of one

parameter's elements will map onto most of another's. Comparing the

relationship between the interior mappings and the "largeoperative" articulatory-pitch

boxes yields significant information. For instance, in the first

"long" section (to #22) we see an increase in the number of mapped

elements within each parameter and a resulting increase in the number of

mapping combinations among the parameters. At #22, moving into the short area

and just partially into the unpitched area affects a striking reduction in the

number of mappings among the parametric elements; moving entirely into

unpitched territory eradicates both pitch and shape, and the only shape left is

the large-scale, accretionary one.

Figure 6: Polymorphia., Long- and short range information exchange and

mapping

This inter-parametric mapping has been so depleted by the move into

short, unpitched territory that even the return to the long and pitched

quadrant at #44 is not sufficient to ensure an immediately corresponding return

to the former level of mapping activity: the number of combinations available

at #44 is minimal, and it takes until #56 before the number of combinations

reaches its former level of #22. And comparison of #'s 46 and 59 in Figures 5

and 6 shows that the increase of interparametric mapping is associated with a

rapid turnover in both timbral and harmonic parameters; this turnover seems to

create an instability within and among the pitch, timbre, and shape parameters

which could well be construed as catapulting the thrust towards concrescence

into the "larger operative" areas of pitch and articulation occurring

between #'s 62 and 63.

Finally, comparing Figures 6 and 2 provides a sense of how concrescence

fluctuates in each piece. In Polymorphia the area of maximum

concrescence appears very near the end; in Hyperprism, towards the

middle. This is most likely the result of each composer's approach to

information, whether conscious or not: Varèse's convergences are

byproducts of the interactions among the event categories, each of which is

primarily concerned with maintaining its own identity in the face of the

others; but in Penderecki the large-operative information itself determines the

course of the inter-parametric events, which have no personal identity save

that of existing within the general thrust toward concrescence.

Bibliography

Breeden, Daniel Franklin. "An Investigation of the Influence of the

Metaphysics of Alfred North Whitehead Upon the Formal-Dramatic Compositional

Procedures of Elliot Carter." DAI, 37 (1976), 678A (University of

Washington).

Penderecki, Kryzstof. Polymorphia. Celle, West Germany: Hermann

Moeck Verlag, 1963.

__________. Polymorphia. Cond. Henryk Czyc, Chorus and Orchestra

of the Cracow Philharmonia. Philips, 839 701 LY, n.d.

Schuller, Gunther. "Conversation with Varèse." Perspectives

of New Music, 3 (Spring-Summer 1965), 32-37.

Stempel, Larry, "Not Even Varèse Can Be an Orphan."The

Musical Quarterly, 60 (1974),46-60.

__________. "Varèse's 'Awkwardness' and the 'Symmetry in the

Frame of Twelve Tones': An Analytic Approach." The Musical Quarterly,

65 (1979), 48-66. Varèse, Edgard. Hyperprism. New York: G.

Ricordi & Co. 1924.

Webern, Anton. Concerto, Op. 24. Vienna: Universal Edition, 1948.

Whitehead, Alfred North. Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology.

ed. David Ray Griffin and Donald W. Sherburne. New York: The Free Press, 1978.

[1] In addition to the chromatic segments, Hyperprism uses major

thirds, which are discussed later in the paper. (See p. 108.) Rarely, Hyperprism

will employ quarter-tones, but evidence suggests that Varèse

considered these part of the predominantly chromatic segment harmony.

[2] Remarks on the designation of the categories and the identifying

characteristics of each: 1) The piccolo (flute) / clarinet timbre may be

defined as music played by these two instruments whose rhythmic activity will

in general separate it from music played simultaneously by other instruments.

2) The filter event is characterized by two types of behavior: a) a rapid

accretion of several instruments (as if a gate were being opened), such as

occurs between mm. 41-44, and b) a klangfarbenmelodie, such as occurs

between trombone and French horn, mm. 3-12. (Varese himself speaks of filters

in Gunther Schuller, "Conversation with Varèse," Perspectives

of New Music, 3 (Spring-Summer 1965), 36.) 3) The tremolo/trill is

identified by either rapid iteration of a single tone (French horn, mm. 6-7) or

successive repetitions of a short figure having a quick enough attack rate. 4)

The brass event is defined by mezzo and lower brass sonorities (generally),

often with accented or pesante articulation, usually proceeding at a rate

slower than that of the other categories. Additionally, the brass event is

frequently characterized by several immediate repetitions of either a single

pitch or an entire chord. 5) The solo category is characterized by the

texture's thinning to one pitched instrument; additionally, this event's pitch

structure employs both up and down displaced trichords.

If one examines each of the event categories in a strictly-linear,

non-interactive fashion, some curious occurrences emerge. For instance, in

their first appearances prior to the moments of maximum concrescence, the

tremolo/trill events appear to define a cycle: Hns. 6 Hns., Trps., Wnds. 6

Trps., Wnds. 6 Hns.

After the first moment of maximum convergence, the cycle progressively

deteriorates, in conjunction with the overall loss of concrescence throughout

Hyperprism's second half. The piccolo/clarinet event seems to become

increasingly animated upon each appearance; compare this to the brass event,

which begins quietly, builds, subsides, and then makes its final appearance

with renewed life. The most noticeably ordered of the event-categories is the

filtered one. Of the timbral (klangfarbened) filter events, two pairs exist in

retrograde relation to each other: 1) mm. 3-12 and 60-65, and 2) mm. 13-14 and

mm. 28-30. The two accretionary events are roughly equivalent.

[3] The term "concrescence" is borrowed from Alfred North

Whitehead's philosophy of organism. The following quotes on this term, from

Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, ed. David Ray Griffin and

Donald W. Sherburne (New York: The Free Press, 1978) are but a few of the many

which can be culled from Whitehead's own writings: "The coherence, which

the system seeks to preserve, is the discovery that the process, or

concrescence, of any one actual entity involves the other actual entities among

its components. In this way the obvious solidity of the world receives its

explanation." (p. 7) And the following, from p. 26: "In a process of

concrescence, there is a succession of phases in which new prehensions arise by

integration of prehensions in antecedent phases. ...The process continues till

all prehensions are components in the one determinate integral

satisfaction." A most succinct description of Whitehead's notion of

concrescence within the context of metaphysics appears in Daniel Franklin

Breeden, "An Investigation of the influence of the Metaphysics of Alfred

North Whitehead Upon the Formal-Dramatic Compositional Procedures of Elliot

Carter," DAI, 37 (1976), 678A (University of Washington). Breeden writes:

"Whitehead defines existence as an organic 'process,' where the changes

which occur from moment to moment are determined by the positive or negative

'prehension' (acceptance or rejection) of environmental data surrounding an experiencing

'entity.' This prehension is determined by the entity's "subjective aim'

or basic disposition, and results in various 'subjective forms,' or emotive

states. The goal of existence is 'concrescent satisfaction,' or a temporary

oneness with an environment. These moments give meaning, a Being, the Becoming

of existence."

[4] The major third's permeation into the compositional fabric does not

end with its present excursion and subsequent mollification within the brass

category. In m. 17 it has infiltrated the texture so far as to be included

within the tremolo/trill category, as well. In doing so, however, this interval

seems to have overextended and spent itself, for its next significant

appearance is its final one. This occurs at mm. 38-39, and compared to its

situation in m. 17, the major third exists in reduced circumstances: first of

all, it appears in inversion as a minor sixth; and second, it belongs not

within two categories, but only within the brass event, just as it did upon its

introductory appearance.

[5] The rhythmic patterns accompanying Varèse's chord structures

do not point out Varèse's symmetrical arrangement of the pitches.

(Compare this, for instance, with the beginning of Webern's Concerto for

Nine Instruments, wherein the pitch symmetry is made clear by rhythmic

stratification and segmentation.)

[6] Hyperprism restricts itself to chromatic segments and major

thirds, whereas Polymorphia employs quarter-tone, half-step,

threequarter-tone, whole-tone, major-minor-third, and perfect fourth harmonic

structures.

[7] Compare the half-step structure of the canonic glissandi at #11 with

the whole-tone harmony of the identically-canonic glissandi at #13.

[8] The tasto of the #5 band maps onto the highest pitch at #10

and later the banded glissando at #15. Likewise, the ordinario of the

sinusoids onto the banded glissandi at #'s 18 and 19; the ponticello of

the canonic glissandi onto the bands at #'s 14 and 16.

[9] The accretion from #'s 1-22 was built from that section's interplay among

shapes, timbres, and intervals; from #'s 22-38 the accretion was formed by the

interplay between pitched and unpitched "short sounds," and

culminated in the hegemony of the former over the latter between #'s 37 and 38;

the accretion between #'s 38 and 44 was based upon unpitched "short

sounds."

[10] As to form in Hyperprism,

a few comments seem pertinent (see figure 1): 1) Although it may not be correct

to speak of the area of maximum concrescence as a true development section, it

is developmental in the sense that this is the section of the piece during

which the maximum number of interrelationships among the categories is

explored. 2) The first of two roughly-equivalent accretionary moments occurs

just before the area of maximum concrescence, and the second at the end of the

piece: together their placement within Hyperprism appears analogous to codetta

and coda of sonata form. 3) The opening klangfarben (mm. 3-5) iterates

the pitch C-sharp; and immediately after the moments of maximum concrescence, a

gesture unmistakably similar to this opening klangfarben returns (mm.

60-65) on the pitch F-sharp: again, the similarities to sonata form are

striking. These remarks ought not be construed as the author's claiming Hyperprism

to be modeled on sonata form; rather the point is that these are the only

observations about Hyperprism's form that this writer has been able to

make and, instead of demonstrating an historical continuity (keeping in mind

Varèse's remark: "Beware traditionalists from the left."),

seem indicative of an abstruse sense of return, development, and closure.