History and the Word: Form and Tonality in Schoenberg's Phantasy for Violin with Piano Accompaniment1

Larry

Polansky

For

Schoenberg, there is meaning to the word, as there is meaning to the gesture.

The sense of frustration, or perhaps inadequacy, that seems to pervade analyses

and commentaries

of his music

The virtually universal sense of unfulfillment with which musicians are left after reading

any technical discussion of Schoenberg's music... is not

due to the failure of the music,

George

Perle to the contrary, but rather to the manifest

inadequacy of our theoretical

equipment to cope

with its richness and complexity.2

comes not ultimately from the "complexity" of the

work, but from the fact that there is no space left over for the meaningless. No word, no pitch, and no

action occurs without an elaborate historical, internally musical, and logical

cross-referencing. There is, in his life and

art, a semantic saturation that we can only in part reconstruct.

That

Schoenberg was aware, even intimately, of the Brahms Fantasien

(op. 116), the great Bach Chromatic Fantasy, the Mozart Fantasy

in D Minor, the Beethoven Fantasy in C Minor (op. 77)

and Choral Fantasy (op. 80), among other works, is undoubtable.

What his own perception of the relation of his music and reference to

this 'literature, the history

of interpretation of a word, is less clear.

The tendencies

which Schoenberg seemed to embrace, rather, the paths he chose to take late

in life, have been discussed at some length. Classicism, harmonic conservatism,

a return to basic formal principles- all these have been attributed to him,

yet each is incomplete. These ideas describe only single aspects of

his development, for the whole is described

by the work itself.

Thirty-five

years after writing the op. 11 Piano Pieces (not to mention Erwartung), for

Schoenberg to finally and explicitly name a work "phantasy"

is peculiar. It is as if he wanted all that time to show that mastery of forms is

equivalent to being able to return to them with a clear conscience, and then depart from them

once more. The phrasing, structure, even the harmonic language of the violin Phantasy remind one more of these earlier,

free period pieces, than of the later works like the Fourth String Quartet and

the two

concertos. Yet there is a difference: here Schoenberg's reference is not that

of a young composer boldly

stepping out into new realms, new sounds: but rather that of a composer who has

gone so far forward himself that he is in fact an integral part of the history

he wished to refer to. "Violin with piano accompaniment" perhaps

this would not have made

much sense in 1909.

II.

Two "facts"

limit conjecture on the Phantasy: 1)

that it was the last instrumental music

Schoenberg composed and 2) that, according to Rufer's

catalog, the violin part was written first, independent of the piano accompaniment.

With regard

to the first, any consideration of Schoenberg's work must take into account

the composer's own search for musical meaning and enlightenment. not only through the localized consistencies of a single work, but

almost equally through the more globalized intentions

of the entire opus. These intentions are clearly both historical and ontological.

To know Schoenberg solely through the parodistic

styles of the Serenade, even though virtually all characteristics of his

conception and virtuosity are present there, is perhaps

not to know him at all. As is evidenced by Schoenberg's penchant for being his own best

historian, no one can know (or make use of) his development better than he

himself. He both constructed and obeyed it, responding to the apparent,

entertaining qualities

of the Serenade with the abstract austerity of the Wind Quintet; to

the complex angularity of the third quartet

with the lyricism of the fourth; to the astounding complexities and mammoth scope of Erwartung,

Five Orchestra Pieces, and the Book of Hanging Gardens with the Six Little Piano Pieces (op. 19); and perhaps, to a

lifetime of the most severely critical and embracive musical thought

with the uninhibited grace and pure musical-melodic joy of the Phantasy.

With

regard to the second "fact" , that of the

alleged manner of the piece's composition, both Leonard Stein and. Josef Rufer seem to be sure that the violin part was composed

first, but with the piano accompaniment kept in mind throughout, with regard to

both its hexachordal and textural characteristics.

Since Schoenberg wanted to write a phantasy for violin with piano accompaniment and not

a duo, he first composed the entire

violin part alone.... During the course of the violin part,

the row forms which are being used, as well as those which

are planned for the piano part,

are noted in red, green or black pencil.3

Rufer does not

explain how it is known that the violin part was composed first. Leonard Stein, in

his liner notes to the ARS NOVA,, ARS ANTIQUA

recording Inner Chambers, states

it a little differently:

"Schoenberg emphasized this distinction between the

two instruments by writing the manuscript

twice: the first time, for solo violin only; the second time with the piano

part added. Certain calculations concerning

the disposition of the twelve-tone row forms and their transpositions show that Schoenberg was planning the inclusion of

the piano part...." 4

- but again, it is unclear how

the order of composition is known with such certainty, since

presumably only one manuscript exists.

Be that as

it may, the idea is not hard to accept. The piano part has virtually no melodic

figuration, even of a secondary sort. The closest things to a leading melodic figure are

the cadential melody at ms. 24 and the accompaniment ostinato idea at mm. 42-44. For

a composer of Schoenberg's contrapuntal intensity, the rest of the piano part is quite

unusual in its strict homophonic subordination. It has been frequently noted that the

conception of the "accompaniment" is extended even into the row

forms, for Schoenberg often supplies the piano part with the

complimentary hexachord to that of the

violin.

The form of

the piece is organically conceived with whatever extramusical

intentions Schoenberg might have had for the piece (although

Schoenberg's musical conception is so broad that it almost seems as if nothing in his

realm of existence falls under that rubric, which, after all, tells us much more about the

speaker than the object under consideration). The sense of pun, both in the small and the

grand design, is never absent from his work. The naming of the piece, the description of the piano as "accompaniment" , the reflections on and allusions to Brahms, Mozart,

Schubert, and even Chopin and Beethoven, and the meaning of the particular

compositional gesture at a point in his life and

in the history of music when his own tendencies towards classicism were an issue, are

all factors to be considered if the music, that is the score itself, is to be

appreciated

to any degree.

In his

liner notes to the ARS NOVA... recording, Stein calls it a

"multi-sectional structure, with many strong contrasts in tempo, character

and form...." and that " the recurrence

of the opening main section serves to unify the entire piece, much in the manner of a

Rondo or Sonata- as suggested by the following outline: (Ms. #'s supplied by LP)

1

Main Section (A): Grave-dramatic in character (mm. 1-31)

2 First Episode (B): Meno Mosso (ms. 32), Lento (ms.

40), Grazioso (ms.

52) - mostly lyrical.

3 Second Episode (C): Scherzando (ms. 85)- form and

character of a

scherzo.

4 Main Section

(condensed) (Ins. (133) 135) and coda (A2) (ms. 154?)5

It is a tribute to Schoenberg's mastery of the ambiguity

of form, such as that which he admires

in the assymetry of Brahms' phrasing, that no such

outline of the Phantasy can really contribute much to its understanding. Any such sectionalization only describes its own axioms for perceptual distinction- Schoenberg always

knew this and sought to integrate

all the varied parameters of his craft in such a way as to at once clarify form

and at the same time confound the superficial perception

of it.

Form in music serves to bring about

comprehensibility through memorability. Evenness,

regularity, symmetry, subdivision repetition, unity,

relationship in rhythm and harmony

and even logic- none of these elements produces or even contributes to

beauty. But all of

them

contribute to an organization which makes the presentation of the musical idea

intelligible. The language in which musical ideas are expressed in tones

parallels the

language which

expresses feelings or thoughts in words, in that its vocabulary must be

proportionate to the intellect which it addresses, and in

that the aforementioned elements

of

its organization function like the rhyme, the rhythm, the metre,

and the subdivision

into strophes, sentences,

paragraphs, chapters, etc. in poetry and prose.6

-

and in even a more direct statement,

Let me say at once that I am more inclined-

unconsciously, for sure, and often even

consciously- to blur motives, a tendency that will

certainly meet with the approval of

those who feel in music 'life on several levels' and who therefore

prefer to hear a kind of

'counterpoint' between motive and phrase: a complimentary opposition. 7

Even a quick glance at the Phantasy

reveals that at once Schoenberg is paying homage to those forms which he respects in the works of earlier

composers, and at the same time paying

them the even greater tribute of participating in their development by taking them further. For example, mm. 52-63, the Grazioso section, appears to be an almost deliberate paraphrase of traditional ternary form. It is

twelve measures long, in 9/8, with

simple dance-like rhythms (especially the opening and closing four measures)

and seems to be the

only place in the Phantasy where

Schoenberg is willing to relax the feelings of ambiguity. The twelve measures are in clear ABA

form, the last four measures nearly

identical in rhythm and intervallic content to the first four, although many of

the intervals are inverted in the use of the row form

permutations:

Example 1: MM. 52-53, 60-61 (Vln.

part); "Outside" Measures of Ternary Form Compared

However, this local bow to a certain type of clarity is

not indicative of the formal and structural

intentions of the piece:

Ternary, rondo, and other rounded forms

appear in dramatic music only occasionally,

as episodes, mostly at lyrical resting points where the action stops or

at least slows

down- in

places where a composer can proceed along formal concepts and can repeat and

develop without being forced to mirror moods or events

not included in the character of

the material.8

The 'theme' of 'the Phantasy

(which also happens to be the row), is stated in mm. 1-2: and is restated in part, whole, and in allusion at

significant points throughout the piece. At

ms. 32, it serves to introduce the section marked Meno

Mosso (ms. 34) but there is clearly some formal

development prior to that.

The first major cadence occurs at ms. 24, and it seems to me that it is here that the piece first reveals its

affinity not only for the

highly sectionalized Violin Concerto, but even more for the so called

first-period pieces like op. 11 and op. 17 in which formal structure is

primarily effected through motivic distinction. In fact, although the Phantasy

represents, and has been duly recognized as a masterwork in twelve-tone technique, David Lewin's excellent article to the contrary, I feel that by this time Schoenberg had such

great facility with the various manipulations

of hexachordal permutations that he was able to use

them simply as one more

determinant in the formal gestalts: they are not distinguishing as themselves. Rhythm seems to predominate throughout all of his

works, and this piece is no exception. As he does in the Suite (op. 25),

Schoenberg feels the need to demonstrate to history

that row manipulation is a heuristic device to escape the lack of

meaning, through overdevelopment, that

tonality and atonality had assumed. Form is not determined by pitch. Motive and morphology, rhythm, temporal

density, dynamics, and timbre offer the

composer more than enough, and perhaps the Phantasy

is the last time Schoenberg states

his case that twelve-tone technique is indeed an "emancipation",

and not a restriction.

Example 2: MM. 1-2; Violin; Row/Theme

A clear formal break occurs at ms. 25.

After the fermata in the solo piano line, the Piu Mosso enters in clear rhythmic and melodic contrast to the

more songlike first twenty-four

measures. Lewin calls it a "second theme"

and although as in Ives, it is more

like the simplest development of a theme that never occurs but underlies many different structures, it is clearly the prototype for

most of the contrasting material, if only in its heightened rhythmic activity, close intervals, and melodic

density. In a sense then, the

aborted but verbatim return of the first theme at ms. 32, along with the dramatic ritard preceding it, is

a kind of conclusion for all before it, and announces the beginning of a development. But the Meno

Mosso section beginning at ms. 34 relaxes both the rhythmic and melodic density, and one is reminded

of another great Fantasy, the

Mozart D minor for piano, K. 397, where the same sort of dramatic textural contrast occurs so often. C Mozart has to be considered

above all as a dramatic composer"

9 The

section that follows, mm. (32) 34-52, is one of the most

extraordinary in the piece. Like

the Grazioso, it is basically ternary. MM. 34-38(b)10 present a relatively song-like idea, with a rather typical (Brahmsian)

broken chord accompaniment, followed by what seems

to be an even more deliberately Brahmsian passage

(mm. 40-44(6)), with the piano ostinato dreamily

underscoring the slowest violin melody in the work:

Example 3: MM. 44- ; Piano Ostinato

Figure

Here, the term fantasy is interpreted not with respect to

overall form, but in regard to mood.

It is not surprising that the Brahms Fantasien

(op. 116), with all their diverse formal characteristics but clear "modal" consistency were

among Brahms' last works. Measures

(45) 47-51 return to the idea of mm. 34-38b, but the piano clearly signals the upcoming

major structural division at ms. 52 with its arpeggiated

chords in mm. 48-51.

The Grazioso (52-64) has already been

discussed as to its internal formal structure, but now we can see it in its formal relation to

what precedes it. In a kind of free rondo, Schoenberg has emphasized local three part form, with the

thematic return at 32, and

the sectionality of mm. 34-51. In more traditional

terms, the piece up to ms. 52 can

be seen as two episodes, variations, etc. MM, 52-64 can be seen as a kind of

structural pivot and

point of least motion around which the piece centers. That this section is, in itself, highly complex does not detract from the

strong sense of structural completeness

one gets from it and its relationships to the other sections. It is followed by

a short, free, chorale-like interlude

(mm. 64-72) which in register and rhythmic activity (at least in the violin) is closely related to the

"outside" measures of the Meno Mossa (34-51) or that

section which immediately preceded the Grazioso.

The

next section, mm. 72-84, clearly set off by "cadential"

material in measure 71 is a coda to the entire first part of the piece (1-84).

The theme is paraphrased in ms. 72

with some alteration:

Example 4: Ms. 72; Violin; Reoccurence

of the "Theme"

- but its rhythmic and

morphological distinctiveness from the preceding material marks it as a clearly recognizeable

motivic return. The greatly reduced rhythmic activity, along with violin melodic ideas clearly

reminiscent of mm. 34-7, 47-51, and 64-70, make

this a kind of two part mini-recapitulation of the formal and motivic characteristics of the first part of the work. Mm. 82-84 are a clear

ending to this section, cadencing

rather finally in ms. 84:

Example 5: Ms. 84; Vln. and Piano; Cadential Figure

of the " Piu Mosso"

If all that precedes ms. 85 could be considered a

structural unit in itself (A), then ms. 85-154 can certainly be considered a

kind of middle section (B). Although these large formal

descriptions tend to overlook the tremendous inner conplexity

that exists, it seems clear that Schoenberg

is working, as he does in the Serenade and in Pierrot, with forms whose association with

musical convention is only coincidental to him. He viewed these forms as expressions of a larger set of meanings, tonality

being simply one semantic

representation, the twelve-tone system being another- tonality's logical and inevitable replacement. Tonality did not cause the

predominance of the ternary idea, but was rather a parallel result of a

deeper generative idea, that of distinction:

For in a

key, opposites are at work, binding together. Practically the whole thing consists exclusively of opposites, and this gives the strong

effect of cohesion. To find means

of replacing this is the task of the theory of

twelve-tone composition.11

Thus, the "simple" rounded forms he found

himself so comfortable with later on are

not a renunciation of the revolutionalry

formal achievement of works like op. 17, but a

result

of maturation and deep acceptance of law, and his own profound instinctive

affinity with the " cosmos:

Hauer looks for laws, Good. But he looks for them where he

will not find them. I

say that we are obviously as nature around us is, as the

cosmos is. So that is also how our music is. But then our music must also be as we are

(if two magnitudes both equal

a third...). But then from our nature alone I can deduce

how our music is (bolder men

than I would say 'how the cosmos is!'). Here, however, it

is always possible for me to

keep humanity as near or as far off as my perceptual needs

demand....12

Thus the rather startling fact that the Phantasy, a work whose formal intricacies,

rapid character shifts, and high density of

information suggest an absence of a simple large scale structure, can be divided so "neatly" into a three part form (1-84,

85-153, 154166). This is

a result of Schoenberg's intuitive sense of the simplest and most direct, while at the same time creating high levels of

micro-structural activity. One can not help

but compare this "style" with that of the later Brahms, for example

his Capriccio (D minor) and

Intermezzo (A minor), both from op. 116, where a tremendous amount of localized

activity is contrasted to a "simple" encompassing three-part form.

The Scherzando (85-92), Poco Tranquillo (93-116), Scherzando

(117-134), and Meno Mosso (135-153) together

comprise the second major section of the work. Although

there is a fundamentally different rhythmic character present

here, more dance-like and certainly less complex, most of the

material in this section is derived readily from that of the first. The three

against four feel of mm. 34-38b; the melodic ideas of

mm. 125-33, of ms. 47-51, 34-38b, 76-81; and the repetitive ideas of 135-139 are a kind

of condensation (rather than development) of the same idea which has been prevalent

throughout (e. g. yin. ms. 5; yln.

ms. 12a; yin. ms. 27; piano mm. 52-54, 56-7,

etc.). The effect of mm. 135-53 is to coalesce two disparite elements, the repeated pitch and the rather

complicated melodic line, into one unified concept. Almost all

of the ideas in this section are based on this union (even the premature return of

the theme at ms. 143). To reach for stasis of some kind at the end of a highly

developmental section is not unusual, but it is certainly not the kind of

creative convention taught in composition classes. It is a subtle,

highly intuitive gesture which bespeaks a compositional mind of the greatest maturity,

and one to whom the actual traditional forms are not of primary interest, but rather

the nuance of their realization. It is once again a matter of opposites: rather

than climaxing developmental agitation by bringing it

to 4 frenzied conclusion, Schoenberg understands, through his meticulous knowledge

of the "masters" that the most astonishing perceptual effects are

brought about by distinction: stasis in context is as active as

any motion. Gestures of this type are of course well-known, but one of the most breathtaking

(and relevant here) is the section of the Eroica

(1st movement, near the end of the development, mm. 250-280, but

especially 270-280) where, after some of the most complex melodic and harmonic invention, Beethoven

surprisingly relaxes the harmonic and orchestral

motion.

Comparisons

with the Eroica are not so haphazard as

they might appear, for the section mm. 143-153 (of the Phantasy)

brings to mind an even more famous event in the

former, the " premature" entry of the theme,

near the end of the development, in the horn (in the " wrong key" ). The

"reprise" of the Phantasy takes

place ten measures later (at ms. 153). Depending on one's terminology, we

might call this either a coda or a recapitulation. Lewin, in his

analysis of the work almost entirely in terms of its hexachordal "regions" states:

I have divided the piece into three sections.... It

Will be noted that the change of area

at measure

32 corresponds to an obvious major formal articulation of the piece, and

that the AO

area between ms. 143 and ms. 161 1/2 contains a formal "reprise" (ms.

154).13

I do not undervalue the importance of understanding

Schoenberg's more strictly serial intentions in the formal construction of the piece. Ms. 143 is heard as a

thematic restatement:

but, as in the Eroica's horn, some of

the musical parameters are slightly out of kilter". In this case those parameters are octave

transposition, rhythm, and pitch

repetition: in the Eroica - dynamics

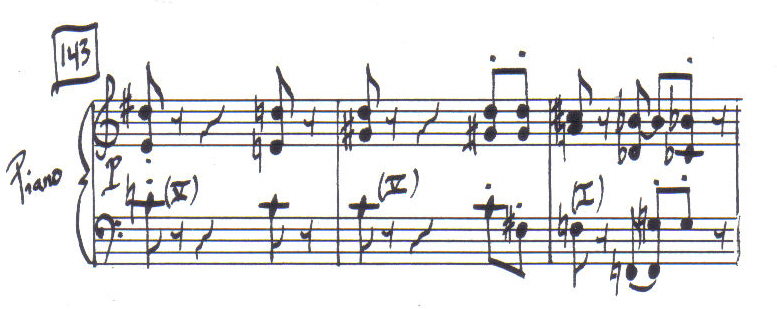

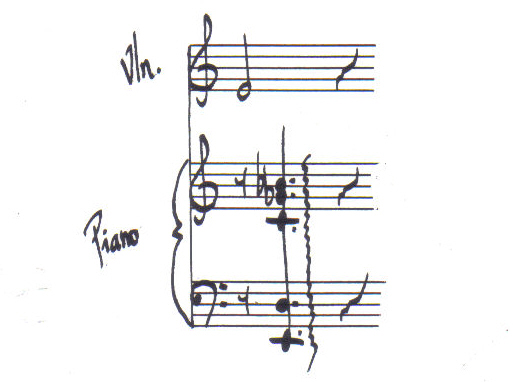

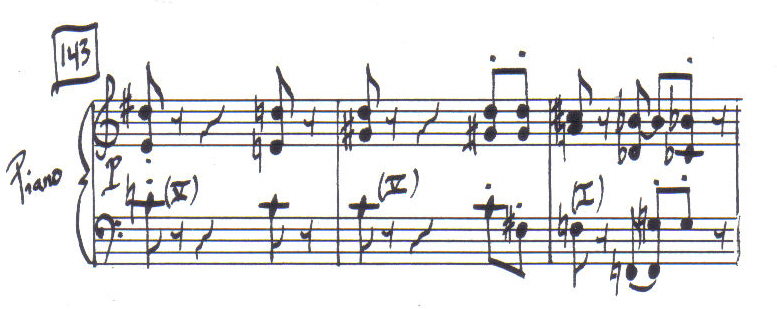

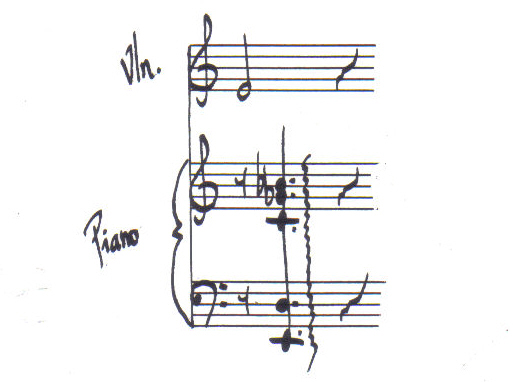

and harmony. To draw the analogy even further, note that the piano harmony (mm. 143-145) acts as a kind of

tonic/dominant in a way that might be

an intentional pun:

Example 6:

MM. 143-145; Piano; Use of "Tonic" and "Dominant" Functions

- (in section III., I will

comment briefly on the "functions" of certain of these harmonic

sonorities).

Not much need be said about mm.

154-166. The gestures are clear and effective. With a nearly literal repetition of the theme (a major second

below, for the original pitches have been stated ten measures previous), reference is quickly made to many of, the

predominant motives of the piece (ms. 158, vin.,

triplet and triplet-like figures

in the piano, and at ms. 161 (second half) a tune closely resembling that of

the "second

theme" (ms. 25)). The work ends, appropriately enough, as Stein puts it,

with the "final

liquidation in double stops, tremolos and repeated notes (bringing) the composition

to a brilliant ending" .14 (from Stein's liner notes).

The row for the Phantasy is chosen, I believe, with some very

definite harmonic considerations in mind. The

order of the second hexachord really depends on what one accepts as the prime of the row, or whether there

is one. Lewin seems to believe that this is not the prime, for the second hexachord is

merely a transposed inversion of the first.

However, since hexachordal manipulation is used so

readily throughout, the actual "ur" form of the row is of little interest, and

probably undeterminable. Stein seems to

support the form I have given, noting as well that the "piano part often complements the given violin

part by supplying the tones of the opposite hexachord, as in the opening phrase". Thus, the order of the

first twelve pitches stated in the violin

part is not of restrictive importance.

Example 7:

Two Hexachords of the "Row"

If we reorder the hexachord (either one) we see some

interesting harmonic characteristics:

A/C#/F

and G/B flat /B

or,

of slightly less importance:

G/B/C# and A/B flat /F.

It is significant that the hexachord contains no major

or minor (" tonic" ) triads, and that the two triads present (augmented and flat-fifth) are

those which least imply a tonal

center out of all possible triadic combinations, since, by Schoenberg's own reasoning, their respective fifths are drawn from the

eleventh and thirteenth partials. Schoenberg's concern with this aspect of consonance (and dissonance) can

be seen easily in his

lifelong devotion to harmonic principles and theory, whether we consider the Harrnonielehre and Structural

Functions..., his music, or his short essays. One fine and interesting example of the latter is the famous

"Problems of Harmony" from Style and Idea where he relates all harmonies not major or minor to the use of partials

higher than the sixth.15

One of the most convenient clues to

the functions of these triads in the Phantasy (aug., b5th, and the chord consisting of a root with a minor

and major third above it, which I will

call the maj/min) comes from Schoenberg himself:

...In my Harmonielehre

I have shown how every diminished seventh chord and every

augmented triad belong to all major and minor keys, and

what is more, in many a

different

sense. This is probably the place to, point out that J. S. Bach in

many 'introductions', for

example, and especially such pieces or parts labeled

'Fantasia' prefers a disposition of the harmonic structure which neither in its

entirety nor even in its detail can be easily referred to a key. It is not

uninteresting that in just such instances these old masters use the name

'Fantasia' and unconsciously tell us that fantasy, in contradistinction to logic, which everyone should be able to

follow, favours a lack of restraint

and a freedom in the 'manner of expression, permissible in

our day only perhaps in

dreams;

in dreams of future fulfillment; in dreams of a

possibility of expression which

has

no regard for the perceptive faculties of a contemporary audience; where one

may

speak with

kindred spirits in the language of intuition and know that one is

understood

if one uses the speech *of the imagination- of fantasy.16

Even

thirteen years prior to the composition of the Phantasy,

such a self-analysis is essential to

our understanding of the work. In constructing the particular row and

compositional texture (piano accompaniment) Schoenberg

makes the grandest of references to the tradition and solves the problem of

how to continue writing in it. Thus, the chordal

accompaniment, which actually sounds as if it has 'tonal' functions, and indeed

frequently does, is never traditionally tonal, for no single fundamental can be

truly established with these chords. In the

piece, the augmented triad acts as a sort of tonic, or point of

reference (though often combined vertically with the maj/min),

and the flat fifth acts as its polar opposite, or dominant. A careful analysis

of the piano part will reveal an overwhelming preponderance of these three

sonorities, in rather undisguised fashion.

Almost all three part simple sonorities are of these types, as are most

exposed chords.

The augmented triad first appears in ms. 10, in a texture

and tempo which makes its introduction quite clear. From then on, it is never

absent. Note also that almost any time a chord is rolled (mm. 12, 14, 26, 46,...) it is the combination of maj/min chord and aug. triad. Sometimes, as in

ms. 51 (Ex. 8) the violin supplies the missing note:

Example 8: Ms. 51; Vln. and Piano; Maj/Min and

Augmented Chord

Note

also the important cadential quality of this measure.

In the phrase previously discussed, mm. 143-45, the aug.

triad at 145 is clearly a point of rest for a chordal

figure beginning on

the maj/min at ms. 143, and of course, the final

sonority in the piano, at ms. 166, is this

same combination of the two. Often, as well, the three sonorities are

used in rapid chorale-like succession when a feeling of changing harmony is desired, in perhaps a deliberate

evocation of the older and tonal homophonic style (e. g., mm. 68-71;

86-91).

Such an analysis reveals

Schoenberg's intense concern with harmony, in that even

with the powerful tools of the twelve-tone system and his virtuosity in it, he thinks

deeply about the harmonic implications inherent in his handling of a form,

which, from Bach through Mozart, Schubert, Beethoven, Chopin, and Brahms, has

traditionally been a vehicle for the composer to explore his own mastery of the

harmonic idiom almost in private, by taking it to new places.

Bibliography

(All

Schoenberg quotations are from Style and Idea).

Lewin, David, "A study of

Hexachord Levels in Schoenberg's Violin Fantasy" ;

Perspectives of New Music; Fall-Winter 1967; pp. 18-33.

Partch, Harry, Genesis of a Music; Da Capo Press, New

York, 1974.

Rufer, Josef, The

Works of Arnold Schoenberg, Free Press of Glencoe, 1963.

Schoenberg,

Arnold, Style and Idea, Stein, Leonard, ed., St. Martin's Press, 1975.

Stein, Leonard, (liner notes to) ARS

NOVA, ARS ANTIQUA recording Inner Chambers (of Phantasy).

1 `I

would like to thank Dr. Alexander Ringer, eminent Schoenberg scholar, whose

fine seminar at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana

motivated this paper; and my colleague in the Music Department at Mills

College, Karen Rosenak, whose critical and editorial

abilities are only matched by her musicianship and generosity.

2 Lewin,

David, "A Study of Hexachord Levels in Schoenberg's Violin Fantasy", Perspectives

of New Music,

Fall-Winter,1967,p. 13.

3

Rufer, Josef, The

Works of Arnold Schoenberg, Free Press of Glencoe, 1963,

p. 74.

4

Stein, Leonard, (liner notes to) ARS NOVA, ARS ANTIQUA recording Inner

Chambers (of Phantasy).

5 Ibid.

6

Schoenberg, Arnold, "Brahms the

Progressive,' Style and Idea, St. Martin's Press,

(Stein, Leonard, ed.), p. 399.

7

Schoenberg,

Arnold, "Phrasing," Style and Idea, St. Martin's Press, (Stein, Leonard, ed.), p. 348.

8 Schoenberg, Arnold, "Brahms the Progressive,"

Style and Idea, St. Martin's Press, (Stein, Leonard, ed.), p. 405.

9 Schoenberg, Arnold, "Brahms the Progressive," Style

and

Idea, St.

Martin's Press, (Stein, Leonard, ed.), p. 411.

10 Note that, in the current edition, there

is no measure 13

(but 12b) or 39 (38b) (3x13). I have no idea why this is so.

Hopefully, it will be clarified in the critical edition, as it occurs in other

scores, and at the present it is far too easy to attribute it solely to

Schoenberg's numerological beliefs-7 in many other works (notably

the Prelude, op. 44) these measures exist! Also, in the Phantasy, mm. 52, 65, etc. exist.

11Schoenberg, Arnold,

"Hauer's Theories," Style and Idea, St.

Martin's Press, (Stein, Leonard, ed.), p. 209. 36

12 ibid., pp. 209-210

13 Lewin, David, "A Study of Hexachord Levels in Schoenberg's Violin

Fantasy," Perspectives

of New Music, Fall-Winter,

1967, p. 20.

14 Stein, Leonard, (liner notes to) ARS

NOVA, ARS ANTIQUA recording Inner Chambers (of Phantasy).

15 There are of course some problems with Schoenberg's

theoretical harmonic ideas. On page 271 he states that "Eb is the 7th overtone of

F and the 13th of G" and that "Db is the 13th overtone of F and the

11th of G". Partch (page 48) accurately points out that, among other things,

the difference between the aforesaid E flat s is 72

cents, and the D flat is 100 cents, or a semitone. Of

course, Schoenberg's thesis that the major scale is derived from the first five

partials of I, IV, and V

(although there is no "IV" in the overtone series) is fundamentally

tenable, but the derivation of the chromatic scale in tempered tuning which is virtually axiomatic to

Schoenberg's entire system of harmonic thought, is intonationally

inaccurate, to say the least.

16 Schoenberg,

Arnold, "Problems of Harmony," Style and

Idea, St. Martin's

Press, (Stein, Leonard, ed.), pp. 274-5.