Family Portraits: “Delbert (great-grandfather)” and Self Interview on the Thirtieth Year

of Smith Publications and Sonic Art Editions

by Sylvia Smith

Gem: anything prized for its beauty and value, especially if small and perfect of its kind.

Webster’s New World Dictionary

of the American Language

Introduction

Family Portraits is an ever-growing collection of musical portraits by Stuart Saunders Smith. Each musical portrait captures in sound something of the character and personality of that particular family member. For instance, Family Portraits: Cubba (grandfather) is a portrait of Cubba’s emotional interior. This portrait is written for trumpet, flute, and 5 percussionists on tom-toms and triangles. The trumpet player is Cubba. It is a lyrical trumpet solo seething with unresolved violence, accompanied by tom-toms which seem to urge him on. About two-thirds of the way through the piece, triangle music is added, as Cubba is joined by his first wife, represented by the flute music. All five percussionists play just triangles as they both ascend to heaven.

Most of the Family Portraits are for solo piano. A few are for mixed ensembles. Family Portraits: Delbert (great-grandfather) is the only one thus far written for solo percussion. In this portrait, aspects of Delbert’s occupation and surroundings are also part of the composition.

Delbert was a woodsman who lived his entire life in central Maine. He worked in logging camps, felling trees for the paper mills of Maine. It was often his job to burn brush and, as an older man, he became the cook for the camp. He worked in the woods until he was in his 80s. It is said that Delbert had a restless nature, preferring hard work and the outdoors. Delbert also had a volatile temper. He could be extremely friendly one minute and extremely angry the next.

The composer remembers being told as a boy never to visit Delbert alone. He describes one time when he did. “One day I passed by Delbert’s house and went up the steps at the back. Delbert gave me popcorn, heavy with salt and butter, and red Jell-o with bananas in it. Then Mother appeared, looking frightened, and led me out of the house. It was rumored that Delbert was “off his rocker.” He would gather up his belongings and set them on fire in the living room, thinking he was back in the woods burning brush.” (Interview with Stuart Saunders Smith, 5/5/05)

Instrumentation

The instrumentation of Family Portraits: Delbert is two small logs that have a definite clear pitch, a woodblock, and some newspaper. Assemble the logs and woodblock with some crumpled newspaper under and around them as if you are building a fire. It is useful to add a few other logs to support the two “musical” logs and add to the theatrical expression, as additional logs and twigs make a more realistic campfire.

Aside from the extra logs and perhaps some twigs or leaves, it is best not to overdo the theatrics with extra props or costumes. It is essentially a musical portrait, even though it has theatrical elements. If you find yourself tempted to add these embellishments, try to do and say more through the music.

Whistling is called for. If you can’t whistle, you can hum the passage. It was said that you could always tell when Delbert was around, because you’d hear him whistling. (Interview with Stuart Saunders Smith 5/5/05)

Hard xylophone mallets are needed, plus a pair of brushes.

Finding the Instruments

Finding the musical logs can be a very enjoyable part of the preparations for Delbert. You can bring some hard mallets with you on a walk in the woods, testing fallen branches as you go. Or, firewood can work well because it is dry. Generally some kind of hardwood yields a clearer pitch, but there is no need to take a scientific approach to your search. In other words, don’t try to figure out in advance what kind of wood it should be and how big the logs should be. Just test them with your mallets and use your ears and your taste, and find two logs that you like. The interval between them is not important, so long as there is a distinct difference in pitch among the two logs and the woodblock.

The Score

Family Portraits: Delbert is a short piece - only 3 or 4 minutes, but a lot happens in that time. Delbert has six sections, although there is no break between any of the sections.

The first section, the opening, begins with a theatrical task lasting 21”. Verbal notation instructs the performer to tear and crumple additional newspapers and add them to the setup, as if to be making the final preparations for a campfire. It is important not to rush the opening. Give it the full 21” so the audience can settle in to what you are doing.

Then, without a break or pause, begin the second section, playing on the logs and woodblock, following the score. The score uses a tablature notation on a five-line staff. The lowest two lines are the logs and the top line is the woodblock. As in most of Stuart Saunders Smith’s music, one is reading mostly “irrational” rhythms - 7’s and 5’s, and occasionally 9’s or 11’s, sometimes with simple counterpoint.

Delbert is a piece that uses limited resources. The compositional challenge in the second section is how to get enough variety from only three sound sources - the two logs and the woodblock - all of which decay rapidly. The composer maintains textural and melodic variety in this section, and the next, by using what I call the “withholding technique”. Paradoxically, this variety is achieved through limiting the instruments even further.

In the first line, only the woodblock and the low log are used. At the very end of the line, a dramatic moment is created when the second log is introduced and given two notes. The second line uses, again, only the woodblock and low log. The next two and one half lines (the rest of the second section) uses just the two logs. This “withholding” technique creates different pitch gamuts which serve as tonal contrasts, maintaining much more interest than if all three instruments were used more or less constantly.

These pitch gamuts also delineate the three macro-phrases of section two. Shorter phrases are created, largely by the use of dynamics. The dynamic markings range from an almost inaudible ppp- to fff+. In each phrase, dynamics build or diminish, followed by a space of a quarter-note rest or more.

Most of the second section is unmetered, and the dynamics become important in shaping the phrases and expressing the cadences. At the end of the second line, a strong cadence is established by diminuendo and at the very end, a repeated rhythm. A bar line is there to fully establish the cadence, the end of an idea, and the end of the woodblock for the rest of this section.

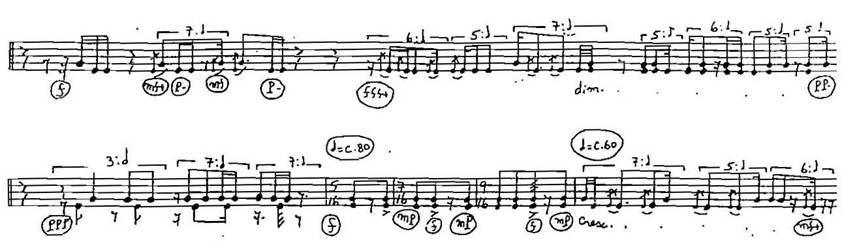

In the fourth line, there is a brief tempo change. The pace quickens and meter is notated for three measures. Since the meter changes in each measure - 5/16, 7/16, 9/16 - and accents fall against the meter, one can assume that the metered section is not used in the usual sense of establishing regularity, but to help drive the new tempo under a more disciplined sense of time (see Example 1). Then the tempo returns to Tempo 1 and is unmetered for the duration of three quarter-notes. Next there are three measures of metered music in the faster tempo, which are in retrograde order - 9/16, 7/16, and 5/16 - as well as in rhythmic retrograde (with a different ending in the 5/16 measure). The diminuendo followed by the fermata and bar line create a second cadence point and end the second section.

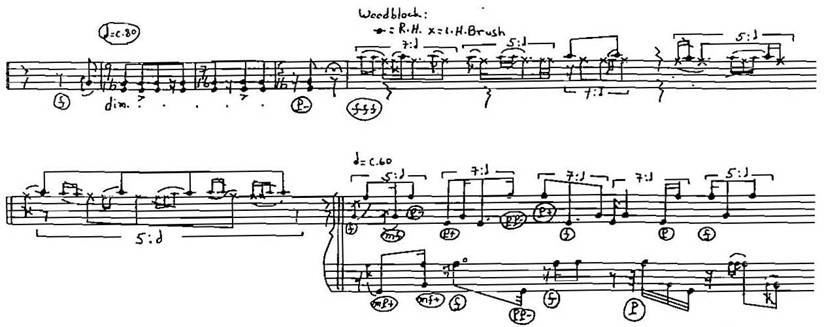

The third section begins after the fermata (see Example 2). Here you change to a brush in the left hand and keep the same hard mallet in the right hand. The two logs are withheld in this section. Striking only the woodblock, the composer creates two layers of music with the two different beaters. This section is marked fff throughout. The right hand with the hard mallet will sound fff. The left hand with the brush, in trying to get a fff, ends up using the height and force of fff, but the results are much softer dynamics and a kind of whipping/singing sound.

Don’t use special brushes outfitted with beads at the end to try to actually make the fff dynamics. Think of the fff as a kind of “force notation” or “speed of attack notation” rather than the resulting sound.

Example 1: Delbert pg. 1, lines 4 and 5

Copyright Sonic Art Editions. Used by permission of Smith Publications, 2617 Gwynndale Ave., Baltimore, MD 21207.

Example 2: Delbert Section Four

Copyright Sonic Art Editions. Used by permission of Smith Publications, 2617 Gwynndale Ave., Baltimore, MD 21207.

The dialogue between the brush (force) and the hard mallet (dynamics) gives this contrapuntal section a highly theatrical and complex musical result. Structurally, this section acts as the fulcrum for the entire piece. It takes a turn into the unexpected, while it is connected in with every other section, either through the woodblock or the brush. Family Portraits: Delbert begins and ends with newspaper sounds. The sound of the brush on the woodblock alludes to (while not actually being) newspaper sounds. The timbral affinity to the newspaper is a pivotal moment on which the piece turns, as it harkens back to the very first sounds of tearing and crumpling the newspaper in the opening section, and forecasts the newspaper played with brushes a little later in the piece.

As a player, when I pick up the brush and begin to play the third section, I think of those moments in the woods when the air is very still and quiet, and the wind rustles only the topmost parts of the trees.

The fourth section begins after the double bar line (see Example 2). You quickly return to the hard mallets and do your best to execute the impossible rhythmic counterpoint. These one and a half lines are, quite literally, impossible to play accurately, and if you are a perfectionist, you might be tempted to put the piece aside because of this section. Its role in the portrait is to represent Delbert in the midst of a nervous breakdown as he drifts further into insanity. The composer refers to this section as “the breakdown section”. You struggle through it, trying to come as close as you can to the impossible counterpoint.

These complex rhythms are notated on two staves. The high level of ornamentation doesn’t allow you to approach it in the usual way, with the right hand taking the top staff and the left hand taking the lower staff. You make a composite rhythm combining the two staves. However, the dynamics, the ornaments, and the close proximity of the figures keep it from sounding like a composite line. The dynamics are less extreme than in section two, ranging from pp- to ff. But they are placed in such an erratic way that one line is constantly interrupting the other. An inner battle is taking place.

It is notated this way for a good reason. No matter how much you practice this section, you will never reach a point where it will sound settled and comfortable. That is the whole point of this notational strategy - to notate a struggle in which you make a valiant effort, but you always lose.

The fifth section begins with a quarter-note rest during which you put down the hard mallets and pick up brushes. You whistle a chant-like melody while you play with brushes on the crumpled newspapers as an accompaniment. You can transpose the tune up or down so that it is in a comfortable range. (If you can’t whistle, you can hum the tune.)

This section is notated with time signatures. However, neither the whistling part nor the newspaper parts make use of the meter implied by the time signatures. The downbeats in both parts are often rests or tied-over notes. This is the first time in the piece that an obvious melody is introduced. Because you can sustain tones when you whistle, slurring is possible, thus creating the possibility of a more nuanced melodic shape. “The time signatures were added after the fact, to help illuminate the phrasing of the melodies.” (Interview with Stuart Saunders Smith, 5/5/05)

After the minor 6th glissando, segue to the spoken text (section six). The text should be memorized so that it comes from you in a relaxed and convincing way. It is your great-grandfather you are talking about. Deliver the text in your own natural speaking voice, without “acting”.

During the text, the performer composes 8 brush strokes on the newspaper to accompany the story. They are composed ahead of time, not improvised. Compose them in terms of articulation, mode of attack, duration, and their placement within the story. Memorize the text first; then add the brushstrokes. Do not let the brushstrokes interrupt the delivery of the text.

Memory Becomes History

We have all had the experience of going into a museum and looking at portraits painted more than a hundred years ago. When they were newly made, an issue would have been how well they represented the subject. How well did it bring out not only their physical appearance, but also their deeper character and spirit?

As time goes on, memory gives way to history. The person in the portrait is gone. Those who remember the person are gone. All that is left are documents and perhaps something of their material world. At this point, the portrait ceases to be a representation and becomes just a painting. One can evaluate it and appreciate it for its formal considerations - as a painting.

For most people, Delbert is in this position. There are only a very few elderly people in central Maine who remember Delbert. For the rest of us, we don’t know him. Most of us have no knowledge of the woods or the work of woodsmen as it was done in the early twentieth century. Delbert’s house and the field of red roses are gone. Delbert has passed into history. All that is left of him are a very few photographs, his hospital medical records, some census data, and this musical composition.

A musical portrait is a kind of programmatic work. The event, or storyline, or in this case the person of Delbert, may have been the initial inspiration for the composition, but with the program or without it, the music has to be worthwhile on its own. The composition must be stronger than the program.

When I began learning Family Portraits: Delbert in the summer of 2001, I looked up Delbert’s medical records, not knowing why, perhaps following an old research habit, hoping to find something that might further illuminate the music. I know almost all of what is possible to know about Delbert. To my surprise, I found that it did not help at all with the interpretation of the music. Except for this: I trust the score. I approach the piece with the confidence that there is no more that is needed than to carry out the tasks prescribed in the score. And these tasks are done by me - through my sense of musicianship and my personal history. The portrait of Delbert is the musical composition, as reliable in its own way as the census documents or the hospital records.

Conclusion

Family Portraits: Delbert (great-grandfather). Can a little piece be a big piece?

There is precedence for it: Density 21.5 by Varèse; Six Little Pieces for Piano by Schoenberg; the miniatures of Webern; collections of songs by Charles Ives. In all these pieces the emphasis is on distillation rather than development. They are what is left of a big piece after all the excess is whittled away. Little giants.

I have performed Delbert more than 100 times. It is a complete and satisfying performing experience - the full integration of music, props, theater, speaking, whistling. Each section has integrity and focus. It has everything it needs, and nothing that it doesn’t need. In short, Family Portraits: Delbert is a gem - small and perfect of its kind.

AFTERWORD

I keep my Delbert logs in a canvas bag for traveling. On one of our tours, we crossed the border into Canada. The customs officer had a lot of questions about the unusual contents of our car. I explained to her that these logs were musical instruments, that we were on our way to give a performance. She wanted to know the value of the instruments. I made up a number, but I wanted to say, “priceless.”

The Family Portrait Series

Earle (father), piano (1991)

Ivy (grandmother), piano (1991)

Sylvia (wife), piano (1991)

Brenda (first-cousin), piano (1994)

Delbert (great-grandfather), solo percussion (1996)

Cubba (grandfather), trumpet, flute, five percussion (1996)

Mom and Dad Together, solo double bass (1996)

Self (in 14 stations), piano (1997)

Ligeia (daughter), soprano voice and piano (2001)

Embden Pond, alto flute and two vibraphones (2003)

Erika (daughter), vibraphone and violin (2005)

Self Interview

Q. Why did you create Smith Publications? Did the idea just pop into your mind one day?

A. Actually, that’s exactly how it happened. I was relaxing in the bathtub one evening after work and the idea popped into view like a calling. Ideas pop into our minds all the time, if we are open to them. This one I acted on.

I had little money for such a venture. I bought a shelf and a file cabinet and a justifying typewriter and found a printer who would give me credit. I had to figure out every step of the way, how to do it, what was needed, for each problem that came up.

I sent out invitations to composers and the first one to respond with music was Pauline Oliveros. I still have her letter from 30 years ago. Others followed. In 1974, I opened Smith Publications with a catalog of fourteen pieces, some very far-reaching music.

Q. Your catalog now has over 400 pieces including every instrumentation and ranging from solos to orchestral compositions. What was your very first catalog like?

A. It was a small flyer that was folded and would fit into a regular-sized envelope. That was important because I mailed out a whole lot of them, being a new publishing company with a small budget.

The music in it was for the most part very unusual. There were two of Ben Johnston’s microtonal pieces, Sonic Meditations by Pauline Oliveros, and Herbert Brun’s set of three solo percussion pieces using computer graphics in the notational system. Various kinds of graphic notation were being explored during the 70s and my catalog included several kinds of unusual notation, plus a piece involving short wave radio.

I was at that time, and still am, interested in the blending of art forms, the connections between, for example, music and poetry, music and theater, etc. In my first catalog in 1974, along with the usual instrumental categories, I had a category called “Flexible Instrumentation and Multi-Media” to give these kinds of pieces a sense of legitimacy and importance.

Q. Why are you interested in multi-media? Is this interest reflected in your work as a performer?

A. My life has been enriched by all the arts. As a young adult, the idea of total theater was very compelling and I was drawn to the music of Harry Partch and his concept of music-theater. At that time, too, that would be the late 60s, Marshall McLuhan’s books were very popular and there was a new awareness of the paradigms implied by the presentation of information. These ideas made me more aware of the presentation of music - that there is always some aspect of theater and dance in a performance, even a strictly musical performance.

About fifteen years ago, I formed a literary group called Out Loud. We met and did performances in my living room. About fifteen or twenty people would come over - various kinds of artists, and we would have readings, then a potluck. I read mostly texts that I had written. I found myself paying attention to the musical aspects of the spoken voice as much as the narrative. There is a natural connection between the speaking voice and music.

In 1997 I founded ConText Performers Collective, a group of performers who specialize in pieces for percussion and spoken voice. That is my favorite kind of performing situation because I get to do both the things I enjoy - speaking and playing.

Q. By and large, you publish American music. Why? Are you a Nationalist?

A. There are some very practical reasons why I focus on American music. English is my only language. And, not being conservatory trained, my education is largely in American music. I know American music best, and this gives Smith Publications a focus.

The other reason, I fear, has been misunderstood by those outside the United States. I will try to explain where it came from. Much of American culture is well-known in other parts of the world, exported to other countries in the form of products, popular music, and advertising, backed up with military power. Having traveled some in Europe, I have felt a little of what it might be like to be on the other end of the exportation of American culture - as a kind of force that is aimed at you. In this sense, we are seen at our worst, not our best. There is hardly a place you can go on the earth where you don’t find American music - popular music - the products of the American musical taste industry.

But in the area of serious musical culture, it is the culture of central Europe that is aimed at us. Composers, orchestras, conservatories, and musicians are thought to be better when they come from Europe. For a while in our history, Americans adopted the German model of education, and German music teachers were sought after. Even though this wave of German music immigration has passed, we still have essentially a German-based curriculum in most conservatories. Many students coming out of American conservatories are hardly aware of our own legacy of serious music and musicians.

I live in Baltimore and we have an excellent symphony orchestra. But performances of American composers are rare, and the star soloists are usually from other countries or were trained in European conservatories. It seems to be not well known that we have excellent composers and musicians right here.

So my statement about being a publisher of American music is largely for Americans to hear. It is my answer to the question Americans often ask: “You mean we have real live composers over here?”

Q. To what extent do you use the profit model in your publishing operations?

A. Because of photo-copying, publishing is a depressed industry. It should be obvious to everyone that one does not go into music publishing for the money. I can think of a great many other things to do that would make more money. And, I publish difficult new music at that.

I don’t do it for the money, but that is not to say that money isn’t important. It is. It is important in the same way that putting oil in the car is important. So you can accomplish what you set out to do.

Q. How is this reflected in the music you choose?

A. When I consider publishing a musical composition - whether it is a work that was commissioned by me or a work submitted to me, I do it in two stages. First, I consider the musical questions. Is it worthwhile as music? Does it stand for something? Does it make the musical world larger, richer? Then, separately, if it passes these questions, I evaluate its financial circumstances. These are separate questions and it is important to keep them separate. In certain cases the financial problems can be solved. But they are still separate questions, the artistic and the financial. You can’t be thinking the piece isn’t very worthwhile because it would be too expensive to produce.

Most of the music I publish was made completely independent of my needs as a publisher. It is my job to either accept it as it is, or reject it. I don’t get involved in changing the piece. I never say, “If you change that ending or leave out that middle section, I would accept it.” It is the composer’s work and either I publish it or I don’t.

Q. When did you first begin commissioning pieces to publish?

A. It was in 1974, almost immediately after I opened Smith Publications. I thought that the vibraphone could be a serious solo instrument. At that time it was thought of almost exclusively as a jazz instrument. I thought it would be most unlikely for a composer to submit such a vibraphone solo. So I asked Stuart Smith, who is also my husband, to write a vibraphone solo, a piece that could really stand alone. The result was the first of The Links Series of Vibraphone Solos that kept developing over the next twenty years.

Q. What other pieces have you commissioned?

A. All the pieces for The Noble Snare were commissioned, beginning in 1987. Far from being a “non-pitched” instrument, the snare drum seemed to me to be full of pitches and full of possibilities as a solo instrument. So I put together a list of composers to ask to write for solo snare drum. It often happens that when drummers write drum pieces, you get a piece full of drum licks not very different from their learning exercises. Not always, of course. So I invited primarily non-percussion composers to write pieces, hoping they would have a new take on the snare drum.

Q. How were your invitations received?

A. I was not quite prepared for the enormous enthusiasm and excitement it engendered. The first person to respond was John Cage. Almost everyone I invited said yes. And they were all so eager to take up this challenge of writing for unaccompanied snare drum. The Noble Snare consists of 33 snare drum solos in four volumes and they are used all over the world. As a collection it makes a very large statement about the snare drum.

In 1992 I commissioned Ralph Shapey to write a piece for flute and vibraphone to celebrate the opening of the Sylvia Smith Archives. I had never heard this combination of instruments before and I thought they would go well together. When I heard the performance of Ralph’s piece at the opening, I liked this combination of instruments so much that I asked two other composers - John Fonville and Stuart Saunders Smith - to compose flute and vibraphone duos for me to publish.

Q. Were the pieces for Marimba Concert commissioned?

A. All of them were commissioned. For Marimba Concert I specifically asked for short pieces for marimba. There are many marimba solos of very substantial proportions, many of them fifteen minutes long. The idea behind Marimba Concert was to offer a collection of marimba miniatures that was stylistically diverse.

Q. You publish only a very few pieces that involve electronics with acoustic instruments.

A. The first time I heard electronic music was in my high school years. I bought a recording of Stockhausen’s Gesang der Junglinge. At that time, I found it exciting and the prospect of electronic sounds with music seemed to add endless possibilities. But over the years, with more experience listening to it, I have come to see electronic music as a dead end.

First, there is the issue of the sounds themselves. Electronically produced sounds are less complex, less rich, monotonous to my ear. There is a disembodied quality to electronic music that makes it virtual music, not real music. I had always thought that composition was stronger than the sounds a composer used, and that in the hands of a good composer the sounds themselves wouldn’t matter. But to my sensibilities, even an excellent composer cannot make up for bland sounds.

Then there is the problem of the loudspeaker. Ironically, while making sounds louder, the loudspeaker seems to diminish the sound, compressing it into a narrower spectrum. The loudspeaker offers up the musical equivalent of tunnel vision.

Another issue comes up when electronic sounds are combined with acoustic instruments. The electronic sounds pale when they are juxtaposed to the sounds of acoustic instruments. As a performer, I have never had a rewarding experience playing with a tape (or CD). Live music-making has a give and take. You are in a relationship with the other players. You shape the phrases as a group. Playing with recorded music is like being in a relationship with a stone. It has no yield.

Q. How have Smith Publications’ editorial policies changed over the thirty years you have been publishing music?

A. At first, back in 1974, I had the idea of being the neutral editor, of representing all styles. Shortly after that, I began to see publishing as a fulcrum in the musical community - as an agency of influence and change. I began the commissions and did not hold back on publishing even more unusual and challenging music. As my own taste is becoming more refined over the years, I have a clearer idea of what I stand for and what I do not. In music and in life in general.

Q. How do you promote your publications?

A. I promote them by showing them and talking about them and listing them in a catalog. Most of the time, the music will sell itself, because it is intrinsically valuable. When I am in an exhibit hall at a music convention, I think of my job as helping people find the right pieces for them, something they will enjoy learning and playing, and will forward them in their musical development. I want to offer people a larger musical world, not a smaller one.

Q. Why did you establish the Sylvia Smith Archive of Smith Publications and Sonic Art Editions?

A. I opened Smith Publications in 1974. By 1990 I had accumulated a great deal of interesting documents. Much of it I had saved because it was directly related to the publications. Some were more peripheral - all kinds of publications, recordings and projects related to the music I publish, as well as unique documents and artifacts sent to me as gifts.

It was too much for my small office. I found myself wanting to throw away letters and books that could be useful to someone doing research on twentieth century music. If I could place these documents in an archive, I reasoned, they would be available for research and free up some office space.

Q. How did you go about organizing your archive?

A. First, I had to go through everything and decide what should be saved and how to save it - what categories to use for documents that are not easily put into categories - and how to organize them to allow access to them. For several months, I went through every emotion that it is possible to feel. I was reading letters from people who had since died, reliving a variety of struggles and misunderstandings, many letters from composers trying to get published, many letters of thanks and appreciation.

As a frequent visitor to the Library of Congress, I gained an appreciation for the organization of the library and an understanding of how history is bound up with and determined by the available documents. And how the organization of the library and the cataloging of documents influences research.

In the thirty years that I have been publishing music, eleven Smith Publications composers have died. The concept of trusteeship weighs heavily on me. Essentially, an archive should do two things that are contradictory. First, it has to preserve and protect the materials in it. At the same time, it can’t just sit there unused. It has to be available for interpretation.

Q. What were your early experiences with music?

A. The experiences that come to mind were my visits to my two grandmothers. One grandmother was the organist for a church in the Boston area. I would visit her and my aunts lived there too, and it was a very musical household. My aunts had ordinary jobs, but the minute they got home their attention was on music. One aunt played the piano. The other the violin. I know now that they all had perfect pitch, although no one talked about it. They would invite me to play duets with them at the piano. Once when I was very little we took the streetcar in to Boston to hear the symphony. They had a television in the house but I never saw anyone watching it. My grandmother also wrote poetry and belonged to a poetry club and so she would read aloud a lot. I loved it there. It was really the best art education I can think of, being in that house.

One of my aunts played in a string quartet that would meet in my grandmother’s house. She asked me to copy out the parts from the score for their rehearsal. I think I was eleven then. I really labored over the parts, trying to make them look just right. When the other women arrived for the rehearsal, they were all excited about the parts I had made. “It looks just like printing,” they said over and over.

Q. And what about your other grandmother. Was she involved in music too?

A. She was a very traditional Mennonite in the old-order Amish Valley in central Pennsylvania. So there was always the sound of horses going by. She raised chickens and pigs and ran what would now be called a bed-and-breakfast. Everything was low tech, although she did have electricity and drove a car. She cooked with a wood stove and did laundry with a big washtub and scrub board every Monday. When you cooked dinner, you would start by building a fire in the stove. It was my job to keep the wood box full. And it was very musical wood when I threw it into the wood box. The Amish belief in low tech living also applied to music. There wasn’t any instrumental music. No radio or records, not even a car radio, no musical instruments. No music at all except what you made yourself with your own voice. My grandmother would sing while she went about her work and we would sing songs with the boarders after supper. And of course on Sunday morning at the church.

It was a world of real sounds, not the artificial sounds we hear nowadays, and I learned to hear very well - to use my ears ahead of my eyes - and trust what I heard. I have a very hard time with the world of artificial sounds - gratuitous background music, recorded and amplified, or electronically produced without any instruments at all. It is everywhere - in every restaurant and waiting room. In my grandmother’s community, if you heard someone singing, there really was someone singing, then and there.

Q. You were invited to Darmstadt Musikinstitut as a special guest in 1988 and again in 1990. What did you experience there as a publisher?

A. The invitation came because I was Robert Erickson’s publisher and he was going to be the featured composer there in 1988. I was not very well traveled and it was my first trip to Europe as a publisher. It was very puzzling to me. People would look at my catalog and then ask me: How is this possible? How can you have Pauline Oliveros in the same catalog with Milton Babbitt? This is irresponsible.

Apparently in Germany, a publisher is expected to ally with one musical movement or another, and get behind it like a political movement. A consistency was expected. My selection of music looked to them like I didn’t know what I was doing, like trying to be a Republican and a Democrat at the same time. This is still strange to me. I think musically, not politically. I think of music as a personal, even spiritual, expression, completely outside the political domain.

Q. What else was new to you in Germany?

A. My family ancestry is Swiss/German. My ancestors were forced to leave during the persecution of the Anabaptists in the years around 1700. So I accepted the invitation to Germany secretly hoping to have some feeling of recognition, however subtle, of the land of my ancestors. I tried hard to connect with the food, the language, customs, their way of organizing space, anything at all. I felt nothing even remotely familiar.

One of the most astonishing events I witnessed was when I was walking back to the hotel after one of the late night concerts. It was about one o’clock in the morning and not one car was in sight. All the Germans stopped at the street corner and waited until the walk sign came on. They were offended when a few of us Americans ignored the sign and crossed the street. They were really very critical of us for doing that. All the time you had the feeling: Who gave you permission to do this, or do that?

I had never thought of myself as an American before. Our government stands for a lot of things that I don’t agree with. But coming back from two weeks in Germany, I saw Americans differently, including myself. Everywhere I saw Americans improvising and being accommodating. On the way home from the airport we passed a traffic accident. Someone took on the task of directing traffic around the accident, setting up flares, before the police arrived. Of course I had seen things like this before, but coming back from Germany I saw it as a particularly American thing to do. Musicians or not, Americans know how to improvise. I felt proud to be an American, proud of our improvisation, and proud to be an American publisher with very dissimilar kinds of music in the same catalog.

Q. What did you appreciate about Germany?

A. There was a rational order to things. Trains leaving according to schedule. This made it easy to get around, not speaking German.

I also noticed the appreciation that German people had for well-made products. Everywhere things were well-made and made of good materials. That was expected. A lot of things were made of wood - children’s toys, household things - where we might have used plastic. And musical instruments, especially those made of wood, were particularly well-made. Good workmanship, along with the recycling attitude, created, at least for me, the sense that there was concern for the future and the well-being of those who will come after us.

Q. Elaborate on the connections you see between the music of Pauline Oliveros and Milton Babbitt. Why do they belong in the same catalog?

A. I see beauty in emeralds and sapphires. They are both gems. Why would I need to choose one over the other?

Q. What are your criticisms of music in general?

A. Most music tells us what we already know.

Q. What is your criticism of percussion music?

A. In general, I would say that percussion music has not yet separated itself out from its military origins. We use instruments like drums and cymbals that were designed for outdoor military drills. Even though we have made musical uses of them now, a great deal of percussion music has the simple meters and limited sense of phrasing of its traditional use.

A lot of mallet music, too, is made with drums in mind - aggressive, rhythmically squared off, melodically unsophisticated. Or we get to play piano transcriptions - compositions that were made with the piano in mind and translated for an instrument that has different capabilities and limitations. Mallet instruments are played emphasizing arm and wrist movement rather than fingers. The arm and wrist movements of the mallet player are better suited to large intervals and skips instead of scales and arpeggios. We really do not yet have a body of literature for percussion that is idiomatic. The problem is only one of imagination.

Q. Have attitudes toward women in percussion changed during your lifetime?

A. I was born in the wake of World War II. It was a hard time to be a girl. Those were very conservative times, with a lot more gender separation than there is now. Separate activities and separate toys. When I was in the first grade and the music teacher would pass out the instruments, a girl could not have the drum. I kept asking for the drum - so did a lot of girls - and only boys could get the drum. By the end of that year, if they hadn’t learned it already, all the girls knew that asking to play a drum was the equivalent to a boy asking to wear a dress. So my first instrument was piano.

As a young woman, the talk we heard about women in percussion centered around physical strength and temperament. It was said that women were not strong enough and didn’t have an aggressive enough temperament to be successful in percussion.

Years ago in percussion ensemble it was the typical situation - two girls, twelve guys. Brenda and I were always ready with our parts, we always came in right, we played musically. But, we were always jumped on for mistakes we didn’t make, and passed over for the special parts. None of the special coaching came our way. The difference was that we were relaxed at our instruments, concentrating, waiting for our entrances, without the aggressive body-language of the young men. Neither of us signed up for the ensemble again, and Brenda dropped out of percussion. None of use were sophisticated enough then to be able to say what had gone wrong.

I look back on this situation as a missed opportunity for all. The director, I am sure, had no idea he was being unfair. He really was a very nice man and took pride in having a mixed-gender ensemble. But he mistook being relaxed for being unprepared, while seeing male behavior as being fully engaged in music and the model for all of us to follow. So he created a self-fulfilling prophesy about women being unsuited to percussion, and in the process he lost two very good players.

Q. What about in publishing? Are there particular problems you run into being a woman?

A. Most of the laws restricting women from owning and inheriting property have been repealed, so, legally, it is easier now for women to create businesses and cultural institutions. I don’t ever take for granted that I can open a checking account or own a car and a house in my own name without having a husband or father sign for me. It was not that long ago that we couldn’t.

Socially, however, it is still difficult for women. We rarely get the credit we deserve. People sometimes assume that my husband is the owner, even though he has no part in Smith Publications. Or they ask, “Where’s the boss?” when they are looking at the boss! If I am invited to a reception as a publisher, and I bring my husband along as my guest, it is too often assumed that he is the invited guest bringing along his wife. My women friends who own businesses say the same kinds of things happen to them.

Q. Is there still a need for music publishing, given the proliferation of composer websites and the ability to print scores from the internet?

A. Music publishers are needed now as much as ever. Anyone can make their music available on the web, and it is considered a good thing, and it is a good thing. But we now have available more music than we can possibly listen to and evaluate. It is available to us undifferentiated in terms of quality, and this puts an enormous burden on the consumer to sort it out.

Of course it is my job to publish music. But it is also my job to NOT publish music, to say no to music that is not worthwhile. With published music, some kind of sorting out has been done. Someone, who could say no, has said yes to this music, and has put their money and their reputation behind it.

Q. What is the future of radical new music in America? Do you still publish radical new music or is the music you publish fading into history?

A. A piece of music fades into history to the degree it was made as a fashion statement. Fashion always fades away or it wouldn’t be fashion. When the fashionable part of a musical composition fades away, it is easier to hear it for what it is. If a piece is very fashionable, there will come a time when it is as exciting as an old pair of platform shoes.

This is what the “test of time” is all about: will a piece of music outlive its fashion statement? For a piece to stand the test of time, it must have as little fashion as possible - without clichés, without political motivation, without being part of a movement or a bandwagon. This kind of piece is often difficult to talk about, difficult to pin down. This is the kind of piece I always hope to find. This is the kind of piece I like to publish.

Q. How do you know so much about fashion?

A. Before I became a publisher, I was trained in fashion design. I worked for many years as a costumer for theaters and opera companies, and I made clothes for specialty shops. Through my work designing clothes for people, I discovered that fashion has to have scarcity for it to work as fashion. It has to be able to create an artificial division between those who have it and those who don’t. When you can make anything you want, fashion loses its meaning. It becomes very clear that fashion has a life of its own, separate from the clothes.

Q. What future do you want for music in our society?

A. I still long for the musical world of my grandmothers. Where music is something you make and do. Where music is when someone sings or picks up an instrument and plays it. Where music is both an everyday activity and an extremely special event.